This was written quickly but enthusiastically during the early months of the pandemic and previously published on a short-lived version of NR MINT. I abandoned that website, so I’m reprising the piece here. I just now made a few revisions, nothing substantial. Were I to revisit the music, I’d probably want to change some judgments and would likely find analytical mistakes. But I think it’s a good piece.

Pitchfork’s “Over/Under” is a web series in which musicians and other celebrities are asked to decide whether various phenomena, practices, and people are over- or underrated. Smartly designed, shallow, and addictive, it’s a good thing to watch once you’ve given up on self-improvement. In one episode, Mac Miller, having already plumped for cunnilingus and espresso, is asked to weigh in on Barbra Streisand. “I don’t know any Barbra Streisand music,” he says, humble and smiley, “but, like, I feel like she’s awesome.” Miller, who died in 2018, was twenty-four at the time of the interview. His hunchy approval might not have been generationally representative, but my anecdotal evidence suggests that, compared with that of Streisand’s few comparably megaselling coevals, all of them more or less rockers, her music has made a modest impression on people born after 1980, even though many of its signatures (bravura, eclecticism, independence, amplitude) have marked much post-1980 superstar pop through direct or indirect influence. At the turn of the century, Streisand was still history’s top-selling female recording artist.i She has since been surpassed by six women, three of whom (Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, and Celine Dion) pursued, at times and to various degrees, a Streisandian course, as have many artists regardless of gender. Others, not equipped to evoke Streisand’s moon-shot singing, have noted her model of multidisciplinary ambition and insistence on autonomy. Few Americans around my age (b. 1970) could avoid first-hand exposure to Streisand’s music as completely as Miller did. But many, I’ve sometimes proselytized, targeting straight men, have experienced her not as one of the handful of truly great artists to emerge in the sixties but rather as an overhead everpresence requiring infrequent and disgruntled attention, like a smoke detector.

I spent the past few weeks, during the dread spring of 2020, working chronologically through Streisand’s first two decades of solo albums, skipping all but the most central cast recordings and soundtracks and saving her interesting but less monumental later recordings for another pandemic. Some of these albums are longtime personal favorites; some were previously unknown to me. Streisand has a reputation for perfectionism, or at least fastidiousness, qualities that have yielded classics but not a corpus of consistent merit. Her work might be best appreciated through a playlist numbering in triple digits, but she’s an album artist. Her original presentation—Broadway-based, cabaret-hatched, jazz-tinged adult pop—derived from genres for which the LP had been an artistic and commercial boon since the early- to midfifties, and Streisand’s principal recording format has always been the album. These albums are overabundant but not homogeneous; some seem to have been spurred most of all by contractual obligation, but each is distinct. All have points of interest and virtues, such as lead vocals by Barbra Streisand. She’s on one hand a principled, shot-calling empire-builder with a self-protected aesthetic; on the other, a flexible collaborator with an anything-goes streak. Although her music has been intelligently anthologized—2002’s The Essential Barbra Streisand is a decent survey—her hit singles aren’t in each case her best advertisements. Her greatest performances wait on strange, spotty albums as well as on too few start-to-finish masterpieces.

Though my early memories of hearing her music are somewhat misty and watercolored, I’ve been drawn if not loyal to her music since the late seventies. It was only last year, however, that I started routinely to have physical reactions to her singing. Some dazzling legato phrase, inspired improvisation, or go-for-broke high note would bring on champagne-like effects, tingles of euphoria, and laughter of recognition reminding me I must still be a humanist. Such intense experiences can breed devotion and bar discernment. I’m not that kind of fan. My tastes in songs and styles often diverge from Streisand’s. As I carry on below, I’ll try to disclose my general preferences and aversions, so the reader can gauge and sometimes ignore my endorsements and dismissals.

°

Streisand was born in Brooklyn in 1942 and raised in humble Flatbush circumstances. Her father, a high school English teacher, died of an epileptic seizure shortly after her first birthday. “No father, good voice. That was my identity,” she told New York Times classical critic Anthony Tommasini in 2009.ii Her mother, who worked as a secretary to support the family, later remarried, but Streisand had a contentious relationship with her stepfather and a worldview remote from her mother’s (“She’s a very simple, nonintellectual, nontheatrical person who lives and breathes,” she told the New Yorker in a “Talk of the Town” piece from ’62).iii On graduating from high school, Streisand lit out for Manhattan with acting more than singing aspirations, living independently and peripatetically starting at age sixteen. (According the US Census Bureau, the median age of high school graduates dropped, between 1950 and 1960, from 18.4 to 18.1.iv During this period, it seems, students were less likely to be held back than in previous periods, and perhaps in some districts students were more likely to skip grades. This may be mere coincidence, but I talked to a friend whose mother, roughly Streisand’s contemporary and raised in an outer borough, also graduated from high school at sixteen.)

Not unlike her character in Funny Girl, the stage and screen musical patterned after the life of Fanny Brice, Streisand was sometimes told, or she gathered, that she was insufficiently attractive and too obviously Jewish for prominent parts. The producer David Merrick, who was at one point attached to Funny Girl and who was himself Jewish, reportedly had commercial concerns along these lines. He gave in.v If it’s now difficult to square the ugly-duckling aspect of Streisand’s sixties image with her beauty, that’s partly because Streisand, who refused rhinoplasty and other measures to conceal her Jewishness (an early Variety review said she needed a “schnoz bob”), and on the contrary made her Jewishness central to her appeal, helped democratize beauty standards, as Camille Paglia, Neal Gabler, and others have pointed out. Owing partly to obstacles of sexism and anti-Semitism, Streisand, apparently as a backup plan, switched her focus to singing—clearly her more innate talent—with an eye toward opening doors to her more deeply felt acting dreams. Like most pop singers, she had no formal vocal training, though there was one aborted lesson. An early boyfriend, the actor Barry Dennen, hipped her to Billie Holiday, Ethel Waters, Mabel Mercer, and other singers of preceding generations who informed Streisand’s out-of-step style, but she was never under the spell of a single artist and doesn’t seem to have passed through an apprentice phase as an imitator.

She didn’t suffer long in obscurity. Talent, we sorrowfully report, isn’t unfailingly rewarded, but an ambitious singer of Streisand’s acumen and instincts would need to run into pretty hard luck not to at least go pro. Before long she was a nightclub attraction in thrift-store clothes. She started at the Lion, a Greenwich Village club where she established her career-long connection—aesthetic and political—with a gay audience and sensibility. From the Lion she moved on to bigger rooms such as the Bon Soir, where her first album was originally to be recorded. She made several TV appearances in the early sixties, performed in a quietly received revue mentioned below, and in 1962 had a show-stealing role as Miss Marmelstein in Harold Rome’s Broadway musical I Can Get It for You Wholesale. (Streisand’s 1991 boxed set, Just for the Record, includes her Wholesale showstopper and many rarities.)

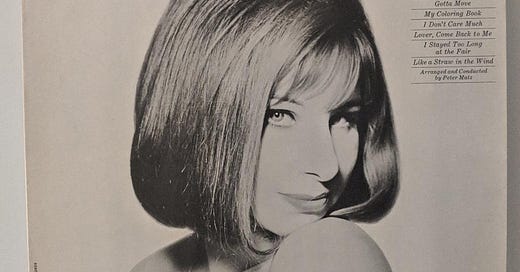

So while she was only twenty when her solo LP debut, The Barbra Streisand Album, was released in early 1963, she was already a seasoned performer and a rising star. Streisand’s voice would mature and improve—her upper register would lose much of its edge, for instance—but the first album shows her to be accomplished rather than promising. The album’s precocious virtuosity and knowledge of its antecedents puts it in company with prodigious young-adult debuts such as Wynton Marsalis’s self-titled release of 1982.

In a rare assertion of independence from a young interpretative pop singer, Streisand convinced Columbia Records to let her choose or green-light her material and control her albums in other ways including jacket art and design. The songs from The Barbra Streisand Album were mainly drawn from her club sets, and their blend of familiarity and novelty, artifice and naivety, high emotion and broad comedy betray the program’s cabaret origins. Any mainstream pop singer of the period would have been in dialogue with Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, and Judy Garland. Certainly, Streisand had studied Garland’s self-deprecating stage banter. But Streisand doesn’t follow their canon-forming albums—such as Sinatra’s Capitol releases, Fitzgerald’s songbook series, and Garland’s Carnegie Hall concert—by concentrating on distinguished prefifties material by Berlin, the Gershwins, Rodgers and Hart, Porter, Kern, and others responsible for what would later be called the Great American Songbook. (I dislike the term.) Streisand instead pulls from new and relatively recent musicals (two from The Fantasticks, whose first production opened in the Village a few months before Streisand hit the Lion), revives obscurities by Rodgers and Hart and Cole Porter (1958’s patter song “Come to the Supermarket in Old Peking,” better left to obscurity), refashions tunes from the late twenties and early thirties, and bookends the album with two well-known songs of the fifties. She values wit, elegance, theatricality, and at this stage eschews sentimentality. “I don’t like mooshy love songs,” she told the New Yorker.vi

The repertoire’s nightclub origins are further demonstrated by frequent maneuvers toward roof-raising. From the start Streisand was compared to bygone or mature stage-trained singers and singer-actors. Harold Arlen’s liner notes for the debut mention Helen Morgan and, setting the stage for the in-the-works Funny Girl, Fanny Brice; Ethel Waters, mentioned above, is another Streisand polestar. As these influences suggest, much of Streisand’s work emphasizes the histrionic element of song interpretation. For Streisand, we’re often reminded, every song is a role. “I’m a singing actress who likes to create little dramas,” she told the New York Times’ Stephen Holden, one of her most astute critics.vii All singers are actors in a way, but there’s a spectrum. Ella Fitzgerald rarely seems preoccupied by characterization and sometimes doesn’t seem to care overmuch about the lyric; her concerns are musical: she wants to enunciate the words and sing the melody in perfect tune, improvise inspired alternate melodies, and let the listener hash out emotional transactions with the song itself. A song scholar and performer such as Michael Feinstein, though more interested in emotive devices than Fitzgerald, also serves more as a conduit between composer and listener. In any interpretative art, maybe in any art at all, so goes one of the dilemmas: whether to be transparent or transformative, sly or assertive. Whatever approach a singer takes, the listener might denounce a misreading. Because Streisand’s interpretations tend to be actorly, and because her voice is both distinctive and famous, she’s instantly recognizable as singer but not as persona, more like Bob Dylan than Bing Crosby.

She rarely directs herself toward understatement. Not every gesture translates to the nonvisual medium. While returning to Streisand’s first albums, I also reread Susan Sontag’s famous 1964 essay “Notes on Camp.” I won’t pretend to authority on Streisand’s relationship to Camp, but it seems safe to say her work approaches it from different vantages. To use Sontag’s terms, Streisand’s debut, self-aware and distant, has little to do with “the sensibility of failed seriousness,” though that will enter the picture later. Streisand’s early work does have much to do with “the theatricalization of experience,”viii a love of artifice and play, a refusal to be stuffily serious, aloofly sexy, elegantly cool (especially in her early work, Streisand’s glamor is both real and satirical). Muchness is crucial to her mode, but more importantly she wants to draw almost orchestral dynamics from her voice: crooning and belting, microphone-dependent coos and for-the-rafters high notes, conspiratorial asides and sumptuous runs, frazzled inhalations and subtly pronounced closing consonants, comic growls along with swelling notes that vibrate across bar lines. Even at twenty, her breath control was amazing.

As she got older, Streisand would become still more adept and at mixing her chest and head voice. Classifying singers according to the vocal types used in classical music is tricky and, to my mind, not always relevant. It can seem like an effort to give pop and jazz singers a promotion they’re not seeking, even singers, such as Streisand, who have dipped toes in the classical repertoire. People more expert than I on vocal technique are better equipped for those debates, anyway, but you can think of Streisand as a mezzo-soprano whose lower extremes are more like those of an alto. If, during the long prime of Streisand’s voice, you were writing a song expressly for her to sing (I am now disclosing a fantasy), a wise tessitura (the general range of a melody) would be around G3 (the G below middle C) to D5 (a ninth above middle C). That would showcase her voice without strain. But if you wanted the melody to travel further, she could comfortably hit notes below and above that range. There are lots of strong, warm E3s on her recordings and notes lower still, and she can sustain a G5 with great power and get at least a third higher with less. (I have a love-hate relationship with YouTube videos tracking a singer’s range through edits of multiple recordings; relatedly, I’m often driven to tears by the YouTube comments that unfurl under music videos and pirated rips: the tributes to deceased loved ones, the needy collective passion, the helpless nostalgia.)

Listeners keenly sensitive to intonation and tone will find fault with Streisand’s upper register; I’m more a “feel” guy and in most things neither hung up on nor capable of recognizing perfection. I’m also a limited singer who goes ahead and sings in public, but I’ll sometimes raise a hypocritical eyebrow over a Streisand note. I once asked a friend, an amazing singer, if she was a Streisand fan. “A little flat,” she said, the first time I’d heard a friend dismiss Streisand because she wasn’t technically good enough. In any case, hers is an expansive if not superhuman range whose display is fun to take in. But the real fun is what she does with it: her inspired phrasing and painterly legato passages, her artful vibrato and idiosyncratic sense of time, how she makes a melody’s highest note exclamatory even it if isn’t so incredibly high. Streisand, a Billie Holiday fan, knows range isn’t really the point. Music isn’t sport.

A stock complaint: Streisand oversings. Such complaints are often made in good faith and justified, as will be admitted below, but it’s also true that women with large and emotive voices can make men angry and uncomfortable. Calls for tasteful restraint can read like calls for suppression. Restraint, if you’ll excuse more equivocation, is a value worth defending, but it’s natural for artists to use all ready-to-hand resources to make things happen, and Streisand makes things happen a lot. If you don’t swoon and pump your fists over her technique and effects—as you might when listening to Coltrane or Hendrix—she’s probably not for you. Maybe you’re crazy.

Her approach on these early albums was a reaction against the nice ’n’ easy aesthetic that flourished in fifties adult pop. (But, foreshadowing: Sinatra’s “Nice ’n’ Easy” was cowritten by a future wheel of Streisand world, Alan Bergman, before he started writing professionally with his wife, Marilyn.) Mind you, an entire decade won’t roll over for generalization. There were dramatic, big-voiced singers of the period: Tony Bennett was often one, and, in his book On Streisand: An Opinionated Guide, Ethan Mordden makes a case for why Columbia’s head of A&R, Goddard Lieberson, initially thought signing Streisand would be redundant because he already had pop records by the outstandingly versatile (but over forty) concert soprano Eileen Farrell.ix As for creating little dramas, Sinatra was an actor and storyteller, in particular on his downhearted, tie-loosened concept albums, and he was sometimes reckless on up-tempo numbers. But it’s true that the innovations of Crosby and Holiday were ingrained by the fifties, and that a relaxed, conversational approach held sway with singers who cropped up in the fifties or were held over from the forties. The phrasing might have been nuanced, but without scads of dramatic reimagining, without much belting of the Ethel Merman school, not always with room-altering personality. Much of the work of Patti Page, Pat Boone, Julie London, Rosemary Clooney (in ballad mode though not when inciting dance), Perry Como, Doris Day, and Jo Stafford can be roughly characterized as restrained. Johnny Mathis, with his arresting timbre and wild vibrato, is in a stylized category of his own, and it’s not surprising to learn that such a singular singer was Streisand’s favorite growing up, as she explained to Stephen Holden. But Mathis’s albums were famous for setting the mood without lowering the bar. In that sense you could say his aim wasn’t to disrupt. On this head, it might be relevant to mention a few jazz singers of the fifties and early sixties who were instrumentalists or writers first and who found cool work-arounds for their vocal limitations or eccentricities, such as Chet Baker, Blossom Dearie, and Mose Allison.

°

To clarify Streisand’s more disruptive aesthetic straightway, she opens her debut with a brash and funny “Cry Me a River,” the Arthur Hamilton song introduced by Julie London’s 1955 hit. The song, addressed to an unfaithful lover returning with hat and declarations in hand, is so good, you wish it were great. Having come up with a memorably colloquial title, Hamilton overworks it, and while rhyming “plebeian” with “me, an’” seems like something Lorenz Hart, Cole Porter, or Johnny Mercer would have risked, they would have given the couplet more context, made it signify as well as amuse. London, accompanied only by Barney Kessel’s guitar and Ray Leatherwood’s bass, sees the song can’t be mined for deep feeling but can be a vehicle for tantalizing understatement and midsummer humidity. The not unfounded cliché that midfifties American pop emanated only from rectories, insurance agencies, and floral shops waiting to be ransacked by rock ‘n’ roll is belied by records like this. Four years later, Dinah Washington stressed the song’s inbuilt blues and worked in some tasty asides but didn’t seem invested. Streisand, supported by arranger Peter Matz and producer Mike Berniker, turns the little song into an operetta. (We should note that Peter Daniels, Streisand’s first steady piano accompanist for her live act, laid some of the foundation for the early arrangements, as is acknowledged on Streisand’s second album.)

In a nod to London, Streisand and Matz start with solo upright bass, the key a step lower than London’s version. Streisand enters with a mouse-like “Now” and ramps up as the song progresses, putting an implied “ha!” after key phrases (“Now you say you’re sorry!” “Now you say you love me!”). Shortly after the two-minute mark, she digs into her Brooklyn accent—“Cry me a rivah!”—revealing one aspect of her voice’s amalgam, its blend of Mid-Atlantic niceties—when she can’t, it’s almost Immanuel; when she can, it’s like Genghis—with outer-borough vernacular. In a 1966 interview with Life magazine, Streisand called herself “a cross between a washwoman and a princess.”x In the third edition of The Rolling Stone Album Guide, Paul Evans writes that “Streisand’s appeal was based on a tension of self-assurance and vulnerability,”xi and it’s this tension, as well as tension between comedy and drama, that makes a performance like “Cry Me a River” such a departure from much of the straight pop of the fifties.

Now the repeated bridge. It starts, “You drove me, nearly drove me, out of my head.” In London’s hit, recovery seems to be complete. For Streisand, especially by the second pass over the bridge, the near insanity either lingers or is freshly remembered. To misquote Van Morrison, eventually she’s both pulling no punches and pushing the river. “C’mon! C’mon!” she wails while the horns punctuate. Like London, she knows the song’s anger is two-dimensional, so she hams it. Rueful laughter, finally a late-stage modulation to the key London used, then a sustained climactic high E-flat, maybe a touch sharp in spots, but remarkable.

In thinking about artists, we shouldn’t always truffle out change and innovation while suppressing continuity and precedence, nor should we strain to historicize every great artist as a self-consciously rebellious innovator in the mode of Woolf, Duchamp, Charlie Parker, or whoever you like. When it comes to enduring superstars, most are genuine eccentrics, which is partly how they sustain our interest, while also being substantially conventional, which is how so many of us can understand them. But Streisand’s singing style and self-presentation were mainstream disruptions—disruptions of the mainstream, that is, pursued within it—a feminist and populist set of articulated and implied demands, and this disruption continued to fuel her music’s raised emotion. “Art that deviates from precedent is, perforce, emotional,” Wayne Koestenbaum writes, “if only because it rejects the prior, the given, the laden. Rejection and refusal are always aggressive, and aggression is the motor of most emotion.”xii

In an alignment not as common as songwriters would like, the album’s finest performance is also its finest song, the dreamful “A Sleepin’ Bee” from Harold Arlen and Truman Capote’s 1954 musical, House of Flowers. Streisand performed it on The Jack Parr Show in 1961, her first TV appearance. Aside from the cast recording itself, a few notable versions precede Streisand’s. Mel Tormé’s rendition, from 1960, is likably swinging but substanceless, and by dropping the introductory verse, he leaves the lyrical conceit rather too mysterious. Tony Bennett makes no edits and gets the mood right, sultry and melancholy, on 1961’s Tony Sings for Two, a set of voice-and-piano duets with his loyal accompanist, Ralph Sharon, and a precursor to Bennett’s bolder midseventies session with Bill Evans. Streisand, unfortunately, also drops the intro verse. The practice is, well, standard, and often helps unlatch showtunes from their shows, but sometimes the intro verse provides important stage-setting more than transitional throat-clearing. Streisand compensates. It’s a beautiful, sophisticated song, a “tone poem” in Ralph Sharon’s view.xiii The harmony is lovely and dense, with salt from altered dominants. The melody doesn’t require a wide range, but it keeps a singer on her toes, balancing lyricism (the most memorable passage is a few ascending arpeggios, not hot-dogging but perfect) with repetition and bluesy chromatic half-steps. Streisand gives the song just enough theatricality (“Maybe I dreams!”) and at a minimum a half-dozen memorably expressive notes.

The Barbara Streisand Album is a startling but uneven classic. My feelings are mixed on Matz. He and Streisand have rapport, and because Columbia wouldn’t shell out the biggest bucks, he works creatively with a stripped-down orchestra, which suits the set’s nightclub energy. But he’s something of a square, and his more bowtied ideas undercut Streisand’s rebelliousness. I’d love to hear these songs with a great rhythm section and four horns. Maybe I dreams.

A few ballads never announce themselves despite much exertion. Though Streisand is a skillful comic actor, the overtly funny stuff here isn’t. The racist Cole Porter tune has been lamented. For “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” Streisand uses mock-operettic trills and whoops and maybe some Baby Snooks katzenjammers out of Fanny Brice, with Matz trucking in the bells and whistles, holding clown horns to our heads in case we act up. Maybe it works in a you-had-too-be-there way. In better news, Bing Crosby’s “My Honey’s Lovin’ Arms” is nicely fitted with one of Sinatra’s ring-a-ding-ding fedoras, while Fats Waller’s “Keepin’ Out of Mischief Now,” possibly touched by Blossom Dearie, swings well enough despite brief background vocals from a couple of tipsy pharmacists. “Happy Days Are Here Again,” best known as FDR’s campaign song for ’32, is here done ironically as a saloon lament. The irony was originally shallow, cooked up for a TV sketch in which Streisand played a woman ruined in the ’29 crash, but it became more multivalent. In Streisand’s first album version, you get economic prosperity and new frontiers overcast by racial and gender inequality, nuclear anxiety, The Silent Spring.

°

In those days, labels churned out LPs like buttah, and by the summer of ’63 we had The Second Streisand Album. (For dates and other information, I often turned to, in addition to my own collection, Barbra Streisand Archives, a long-running website conscientiously maintained by Matt Howe. Where there are mistakes, they’re mine.) Berniker and Matz return, Matz this time recognizing, as indicated above, “additional material” by Peter Daniels. Lyricist Ted Koehler goes uncredited for one tune, but beyond that there’s no glaring evidence of a rush job. Though the first two albums are stylistically of a piece, the second is stronger and darker than the first. There are no novelty songs and many about anger, despair, restlessness, and loneliness. Having scored before with Harold Arlen, Streisand makes half a tribute album: Side One is dominated by Arlen collaborations, Side Two closes with one. Of these, best are “Any Place I Hang My Hat Is Home” and “Down with Love,” the latter a witty blues with lyrics by the great Yip Harburg, this time given a winning insertion of Brooklynese: “Give it back to the boids and bees.”

Few write at an Arlen-Hapburg level, but Billy Barnes’s “I Stayed Too Long at the Fair” is the album’s most gripping song, a simple metaphor artfully realized. Streisand’s interpretation is graceful and empathic. There are two Kander and Ebb contributions: their breakthrough hit, “My Coloring Book,” which has yellowed, and the rapier waltz “I Don’t Care Much,” a few years before it was wedged into Cabaret. The frenzied “Lover, Come Back to Me” is a master class in jazz screaming. Streisand rings more beauty than you’d expect from the schmaltzy Oliver! Ballad “Who Will Buy?” And Producer Matz submits his own song, “Gotta Move,” an attempted feminist anthem penned for Streisand, an up-to-date pop song arranged with ersatz Greenwich Village hipness. The narrator’s search for freedom is weakened by her urge get a new man, but it’s a vision of equal partnership with a new kind of man, “a man who won’t worry ’bout where I go / a man who won’t ask how I learned what I know / a man who will know that you’ve gotta be free / a man who will know when to just let me be.” The necessity of women’s autonomy and the effects of its opposition, as addressed in songs such as “Gotta Move,” and by her roles in movies such as Funny Girl, Up the Sandbox, and Yentl, might be Streisand’s defining theme.

When I worked at record stores, these albums were filed under Easy Listening. Despite their ballads, they’re demandingly energetic, nerve-racking if you’re more in the mood for cocktails and cardigans. The horns blare, the singer belts, the tempos shift to double-time or down to the bluesy swing used in burlesque. They’re obviously the work of a young person, a self-asserting feminist young person no less. A young person, however, steeped in a living but threatened Broadway-based pop tradition. A throwback, then, too, and a beacon for anxious oldsters who saw her popularity as hope that sophisticated pop, conversant with jazz but oblivious to rock ‘n’ roll, could fend of superannuation with fresh talent and occasional bongos. Streisand’s first fame came during a culturally, politically, and musically transitional period—yes, all times are, but a specific one in which the vanguard was refining the terms by which the fifties could be repudiated but the sixties weren’t yet quite the sixties.

Rockers sometimes remember the musically fertile Kennedy era as a fallow patch of division-of-labor commercialism between the original wop-bop-a-loo-bop and the Stateside arrival of the Beatles. Pop is a big tent, one that had been expanded more than toppled and restaked by rock ‘n’ roll. The best-selling albums and singles of the fifties and sixties were rangier and less milquetoast than is often understood by those of us born to baby boomers and their slightly older fellow travelers: parents, programmers, and filmmakers, in other words, who insured our first-hand exposure to Elvis, Motown, and the Beatles but only joked about Pat Boone, Acker Bilk, and the Singing Nun. Anyway, the good records of the early sixties were far-flung: jazz and girl groups and folk and blues and showtunes, Monks and Miracles and Four Seasons. Streisand’s first two records sound like rooted, progressive blasts of energy in an open field, neither Emblems of Youth Culture nor Salvos for the Establishment.

The Third Album was released in February of ’64, the same month the Beatles stormed Sullivan. Now the contrast between Streisand and her rock ‘n’ roll peers grew starker and eventually unsustainable.

°

If someone had troubled to give these early albums proper names, you might know that The Third Album, with a few intrusions such as “Never Will I Marry,” is a collection of ballads. It is well very sung: sometimes overdone, as on “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered,” but even more commanding than before. “It Had to Be You” is especially sensitive, despite one too many grateful, head-shaking exhalations for the close. Still, the album is a retreat. Berniker again produces, but Ray Ellis and Sid Ramen have joined the team as arrangers, making Matz sound like Gil Evans in comparison (except he doesn’t). Ellis, whose many credits include Billie Holiday’s Lady in Satin, lays on the industrial orchestrations, including queasy choral embellishment up top. I know Ellis can be good, and his work here isn’t destructive, but it’s a close call. The other arrangers don’t quite come through with palette-cleansing. A few tunes—“Draw Me a Circle” or the warhorse “As Time Goes By”—probably shouldn’t have been invited. A Salvo for the Establishment, except with water pistols filled with pancake syrup.

A few months later, the original cast recording of Funny Girl was released by Capitol, one of a few Streisand-related albums that slipped away from Columbia, which later nabbed the 1968 soundtrack. For this survey, as mentioned, I’m focusing on solo Streisand’s solo work, avoiding many of the albums that accompanied stage-and-screen shows, not my main bag anyway. It would be silly, however, to sidestep the landmark Funny Girl. In the interest of comparison, let’s briefly jumble chronology: Like most people, I’m familiar with the work mainly through the film adaptation, directed by William Wyler with production design by Ray Stark, who had championed Streisand from the jump and prevailed in producing the stage production. The show had a long, stumbling, and fractious gestation. Streisand’s performance in the film is heroic: hilarious, seductive, musically as awesome as Mac Miller guessed, affecting even in the gummy maw of an underwritten romantic plot and a listless second act. In the movie, I even love her lamppost-twirling rendition of “People,” about which song I’m otherwise misanthropic.

The cast recording, naturally, is a better representation of the Broadway show’s final conception and music, as composed by Jule Styne with lyrics by Bob Merrill. A one-day session in the then-standard practice, the cast album is nonetheless slightly better than the more elaborately produced soundtrack. Both have selling points and defects. Funny Girl is Streisand’s vehicle in any guise (there can be no real revivals, only tribute shows), but her fellow cast members from the stage are sparkier than those on the soundtrack. It doesn’t matter much: “If a Girl Isn’t Pretty” is the only standout ensemble number. The orchestra, too, is hotter on the cast recording; the movie band suffers from bloat. Streisand’s earlier performance of “I’m the Greatest Star” is by inches funnier and more exciting, though both are tours de force. You might expect the cast recording, made in the early days of the show’s vindicating success, to sound fresher, and it often does, but then again the soundtrack’s whole-box-of-crayons “Don’t Rain on My Parade” is more joyful than the original. Each of its vocal moves, from pellucid to gutbucket, is so perfect and well-known, no other studio version sounds quite right.

Several songs didn’t survive to see the movie or soundtrack. These weren’t uniformly unhappy casualties, but the original finale, “The Music That Makes Me Dance,” is missed, most of all the lovely early miles of its gradual climb. The film closes instead, though also grandly, with “My Man,” the ballad popularized by Fanny Brice herself and recorded earlier by Streisand (I knew this chronological disruption would lead to trouble). One of the great examples of her actorly singing, her dedication to Amazon-wide dynamics, and her preference for rubato, Streisand begins the song bereft and fairly quiet, and builds, in its last verse, to one of her most electric notes, the long Eb5—the phrase she’s singing, aptly, is “all right!”—preceding the growled reading of “What’s the difference if I say …”

The movie honchos also commissioned new material from Styne and Merrill, who delivered the funny “The Swan,” which Streisand makes very funny, and the exquisitely sung title ballad, which is not, to add to the confusion, the bubbling-under single Streisand released in the fall of 1964, one of the many Styne-Merrill numbers cut from the original show.

That brings us back to ’64. In the spring, Streisand had her first hit single, a version of “People” recorded for Columbia by the Matz-Berniker team. It’s extremely accomplished schlock. A more complicated lineage should be mapped out, but, with later hits such as “Let It Be” and “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “People” helped establish the impressively sung, important-sounding modern middlebrow ballad that extends through “The Greatest Love of All” and beyond. I don’t mean to say its influence has been strictly pernicious. The like-named album came in the fall of ’64, produced, except for the title song, by Robert Mersey, who, following The Third Album’s wrong turn, keeps things frumpy and suburban. I suppose we should remember that Funny Girl was a tremendous hit and that Streisand wasn’t replaced in the lead until Mimi Hines, in a shoe-filling break not to be envied, took over in ’66, freeing Streisand to star in the London production. Understandably, the albums produced during the early part of the show’s run suggest secondary concerns. (Would Streisand’s albums be better and more consistently ambitious if she had been more single-mindedly a musician, or did her stage and screen work elevate her albums by making her a more dramatically sophisticated singer?) People opens with Styne and Merrill’s terrible “Absent Minded Me,” a Funny Girl castoff, sick making in Julie London’s earlier version and not much better here. Oversinging a great song can be chalked up to an excess of passion or daring; oversinging a mediocrity is garish.

Few songs justify drama as forcefully as Irving Berlin’s “Supper Time,” the blues-based lament he wrote for the 1933 revue As Thousands Cheer and its star, Ethel Waters. The song, wrenching in every Waters performance I’ve heard, is narrated by a woman whose husband has been lynched, and who now must prepare dinner and inform the children. Berlin’s bridge is ultimately directed to God in a Job-like inquiry into the problem of evil. The lyric doesn’t spell out the context, and the song has sometimes been trivialized—June Christy’s nonchalant version is one example—as if the man has simply skipped town. Streisand’s interpretation, like Ray Ellis’s Hollywood arrangement, has drama but no gravity, blue notes but no blues. Her showboating take on the bridge is misguided. Today, of course—on the subject of today, I’m writing this not long after video emerged of Ahmaud Arbery’s terrorist murder by professed vigilantes—white singers would recognize that “Supper Time” isn’t theirs to sing; it would arguably be anachronistic to fault Streisand on those grounds. Fair, though, to fault her interpretation, and to point out that while Streisand tends to act her songs, she doesn’t painstakingly prepare for every part.

Next came three albums tied to Streisand’s two midsixties TV specials. My Name Is Barbra, from ’65, is a catch-as-catch-can bildungsroman. It restores the idiosyncrasy of Streisand’s first two albums. Matz is back and does excellent work with a large orchestra. The album starts with a series of songs written for or about children, aptly beginning with Leonard Bernstein’s “My Name Is Barbara.” This is a different Barbara, of course, spelled with the freeloading second a, but we can test our imaginative powers. A few short songs are sung in a child’s voice: “I’m Five” and “Sweet Zoo.” I find these hilarious and charming, but I’ve noticed their room-clearing effect on other members of my small family. Side Two’s ballads include a tender “Someone to Watch Over Me” and Streisand’s first recording of Brice’s “My Man.” Though I wasn’t convinced by that three little pigs routine from the first album, Streisand returns to the Disney songbook, with Pinocchio’s “I’ve Got No Strings,” and it’s both a gas and a statement-of-purpose. A delightful album. My Name Is Barbra, Two was released to have something in stores when the special was rebroadcast in the fall of ’65. Few first-rate albums have been motivated in this way. This one does have her puckered, tack-piano-enhanced joyride through the Brice hit “Second Hand Rose.” But that has been widely anthologized. The album closes with a medley of songs about not having any money. Showbiz invented the medley to remind us it hates art, so maybe there’s something fitting about this one: songs about poverty bundled up with an impoverished form’s park-bench newspaper.

°

Color Me Barbra, from ’66 and stemming from the second TV special, brings in new collaborators, including mood maestro Michel Legrand. It’s mostly a dud, though Streisand is funny on the novel “Minute Waltz” and effective on the Franco-American “C’est si bon.”

Legrand returns as arranger, conductor, and co-conspirator for the welcome left turn Je m’appelle Barbra, also from ’66. Legrand’s credit normally repels me, though I have a soft spot for Legrand Jazz, his pleasing arrangements of jazz standards played by an orchestra of all-stars including Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Ben Webster. Je m’appelle is produced by Ettore Stratta, though it’s Streisand and Legrand who lean into each other’s foreheads on the back cover. All but one of the album’s dozen songs are of French origin, sung in English and French. Streisand doesn’t speak French but sings it plausibly. (Having negotiated the purchase of two or three croque-monsieurs in actual Parisian parks, I feel in position to evaluate her accent.) Unsurprisingly, the program includes a couple of the French pop songs once widely known by Americans, including “Autumn Leaves,” the Joseph Kosmo beauty and jazz perennial set to English by Johnny Mercer; Charles Trenet’s “Que reste-t-il de nos amours” (reworked in English as “I Wish You Love”); and Jean Lenoir’s “Parlez-moi d’amour” (“Speak to Me of Love”), popularized by Lucienne Boyer. Streisand’s “I Wish You Love” is a romp, her “Autumn Leaves” uncharacteristically pompous, though Legrand’s soigné arrangement almost carries it. His arrangements are colorful and sympathetic throughout. I was kind of surprised by how groovy and full-throttle the band sounds on Gilbert Bécaud’s “What Now My Love” (“Et maintenant”)—then realized that was the one arrangement by Ray Ellis. As I diplomatically admitted above, Ellis can be good.

Two more songs to highlight: One is Streisand’s first recorded composition, its French lyrics written by Eddy Marnay. A great one for plainly informative titles, Streisand calls it “Ma premiére chanson.” It’s no amateur beginning. And the album has two versions of “Le mur,” written by Charles Dumont and Michel Vaucaire for Edith Piaf, who died before she could sing it. In addition to the French original, the melody and its many building modulations receive an English rejiggering, “I’ve Been Here.” Earl Shuman’s English words were written for Streisand, so we have, after “Gotta Move,” a second made-to-order anthem for Streisand to express her power and independence. It ought to sound like a paeon to celebrity vainglory, but it’s easy to submit to, full of sturdy lines (“The river runs with one remark / Get on your way, it’s growing dark”) fervidly sung. Presumably, the song should bear some responsibility for 1969’s “My Way,” another Franco-American paeon to celebrity vainglory, this time by Jacques Revaux and Paul Anka and written for Sinatra. A song that forever changed the executive retirement party.

Simply Streisand, from ’67, signals a back-to-basics session unencumbered by memorized French or unseen TV sketches. But it doesn’t precisely return to her basics. In approach and repertoire, it was her most jazz-inflected album and would remain so until the 2009 release Love Is the Answer, produced by Diana Krall. Two new producers take over, Jack Gold and Howard Roberts. Ellis arranges with David Shire conducting. Though Streisand isn’t at heart a jazz singer, in her early days she did front combos in small clubs (including a stop at the Village Vanguard), and she’s a gifted improviser whose departures from the written melody often surprise and delight. Here, I detect the influence particularly of Sarah Vaughan and Dinah Washington, and perhaps Abbey Lincoln, though Streisand has listened widely. Sometimes, when jazz is the language rather than the accent, Streisand can seem not quite herself, like she’s trying on a hat she doesn’t intend to buy, on vacation, but she usually sounds good anyway. The album starts, inauspiciously, with a de trop “My Funny Valentine.” The little laugh on the “your looks are laughable” line is unnecessary, but that’s nothing compared with the later excess, a desecration of Lorenz Hart’s painfully cruel lyric. The album gets much better. On “When Sunny Gets Blue,” the Johnny Mathis hit, Streisand starts with four gorgeously legato bars, and continues with inspired melisma, thrillingly exaggerated words, and conversationally musical phrases. When Streisand sings, “Then the rain begins to fall / pitter-patter, pit-ter-patter,” a brushed snare illustrates. (Unfortunately, Streisand’s sixties albums, like almost all pop albums of the day, don’t credit the session musicians, so I don’t know who brushed that snare.) The vocal on “Lover Man” is shakier, but it’s given a contemporary and infectious 6/8 groove, the combo quite happenin’, the pianist maybe hinting at Tyner. The album’s arrangements are too larded with strings for my tastes but smart. An imperfect but excellent album, and the end of a chapter.

Two endnotes follow the first chapter: I’ll pass over 1968’s Christmas Album in Scrooge-like silence—except to say that her madcap, tempo-shifting dash through “Jingle Bells?”—the question mark is hers—is the spank the song demands. My favorite cut from A Happening in Central Park, her first live album and largely A Bummer, is the monologue leading up to “Value,” a Jeffrey Harris tune from a 1961 revue, Another Evening with Harry Stoones, one of Streisand’s early stage credits. There is also another “Happy Days Are Here Again,” well sung but less like Hendrix’s “Star-Spangled Banner” than I’d like.

°

Before delving into Streisand’s transition to newfangled pop, it might be useful to summarize her procedures and preferences through the late sixties. Like Sinatra, like anyone, Streisand wanted to only sing songs for which she had aptitude and affinity, mostly old ones, which of course is why, as a new signee, she sought and won contractual control over her album repertoire. This was a freedom record labels didn’t blithely hand over. Through the first half-decade of her recording career, she continued to pick songs in the way of a club-based interpreter, by finding simpatico material already out in the world. Through Funny Girl and her other theatrical roles, she did arrive first to a number of songs, but with exceptions such as “Gotta Move,” “I’ve Been Here,” and “Ma premiére chanson,” she wasn’t in the business of introducing songs that didn’t originate on Broadway. Publishers and other song-mongers weren’t constantly shopping songs to her and her producers; she wasn’t buying. Unlike great interpretative singers who hadn’t secured their autonomy—Elvis Presley, for instance, during his post-Army years of onerous movie production—she wasn’t compelled to suffer through songs for which she had palpable disdain. She didn’t shy away from material strongly associated with their original hitmakers. But songs such as “Cry Me a River” and “When Sunny Gets Blue” had first charted many graduating classes before she got to them and had been subsequently worked over by various singers. Fanny Brice’s staples were unremembered by younger listeners. In other words, she didn’t do covers, not in the sense of recording faithful versions of songs recently brought out by the competition. She sang her favorites, took on obscurities and songs few expected of her, and, from the opposite pole, she sang standards long familiar or becoming overfamiliar in an age when pop and jazz acts made multiple albums annually and often drew from a common songbook.

Streisand disliked overdubbing her vocal to a prerecorded track, thrived instead on in-the-moment interplay, and though she had performed live with combos, she preferred orchestral backing. Like many pop singers, Streisand doesn’t read music. Sometimes, when musicians confess to this common and manageable illiteracy, they mean they can’t sight-read, though they understand musical notation well enough to pick out a melody or use a lead sheet to check a troublesome note. Streisand doesn’t read music at all. She learns by ear, through listening to recordings and demos, by working around a piano with a composer, arranger, or producer. She’s said to be quick study, as great singers almost always are. She dislikes rigid or ossified arrangements that don’t let her play with the beat or improvise, but she doesn’t tire of performing songs through the years in flexible arrangements. Several of her greatest sixties recordings were of songs she had performed extensively onstage.

By the middle and late sixties, prominent singers of mainstream pop were being pressured to pepper their releases with songs by rock or rock-adjacent acts, resulting in many resentfully crooned Beatle ballads. In this climate, could Streisand—initially uninterested in rock and insistent on choosing her own songs—carry on as a major star while making albums like Je m’appelle Barbra and Simply Streisand? Remaining a major star, after all, was another thing she seemed insistent on. She might have managed that through film, but one doubts big-budget movies and auteur ventures would have come through had the recording career shrunk niche.

To return to Columbia in the actual late sixties, it was, like all major labels, in transition. One spots loyalty in big-time music, but it’s not often financially irrational loyalty. Tony Bennett eventually returned to Columbia in triumph, but he spent much of the seventies recording for independents and for a while was without a contract altogether. Until about 1967, Columbia’s roster was light on artists who appealed to some segment of the rock audience: there was Dion, whose sixties solo sides could stand more attention; Paul Revere and the Raiders; the Byrds; Simon & Garfunkel; Chicago’s the Cryan’ Shames; and, most importantly, Bob Dylan. A lot to build on, but not, even assuming I’m forgetting some pre-’67 Columbians, a lot of acts. In ’67, Clive Davis was promoted to president of Columbia. After scouting the epoch at Monterey Pop, he was charged with negotiating new contracts for Dylan, Streisand, and Andy Williams. Streisand got a million dollars, a truckload, but for fifteen albums. As the sixties wound down, Davis encouraged—perhaps the word is weak—Streisand to update her repertoire.xiv

What About Today? is this gambit’s ill-fated opening move. Wally Gold, then a house producer at Columbia, had cowritten “It’s My Party,” a good sign if not a party you imagine Streisand itching to crash. Streisand dedicates the album to “the young people who push against indifference, shout down mediocrity, demand a better future, and who write and sing the songs of today.” Perhaps this dedication’s last phrase—free of adjectives or adverbs—conveyed Streisand’s tempered enthusiasm for the Beatles, Paul Simon, and Jimmy Webb. They don’t necessary write the good songs of today. (The precocious and sometimes glorious Jimmy Webb managed to write some very bad ones.) It does seem prematurely gray for Streisand to patronize “the young people.” She was then a trustworthy twenty-six, a year and half younger than John Lennon and less than two months older than Paul McCartney. As sang Moby Grape, who debuted on Columbia in ’67, “Hey, grandma, you’re so young.”

The album is split between nonrock songwriters mostly attempting hipness and the actually hip (or at least young) mostly looking beyond rock. With a few in-betweeners. In the first camp (Mr. Jones extending a handshake), three of the songs are embarrassing and irredeemable, including one by Legrand working with Marilyn and Alan Bergman, who to my dismay would become an important trio for Streisand. There are better contributions from the squares, but even with her beloved Harold Arlen, Streisand strains, overreaching and in spots pitchy on the faux gospel “That’s a Fine Kind o’ Freedom.” (Oh, if you’d like more of Streisand singing Arlen in the sixties, she appears on two songs from 1966’s Harold Sings Arlen. As a duo, Streisand and Arlen charm on a beat resurrection of “Ding-Dong! The Witch Is Dead.”) Bacharach-David, unimpeachable hip even in white loafers, fare well with Streisand’s “Alfie.”

Most of the younger set’s tunes were presumably selected for using harmonic palettes and sundry devices proceeding from music hall, jazz, Broadway, and movie music—stuff, in other words, Streisand could dig into, recognizing kindred old souls. She and Gold mostly err by overselling the jokes. Simon and Garfunkel’s original “Punky’s Dilemma” is funny because its absurdist wit is delivered in a Jobim purr. Here, when the lyric mentions a piano, a piano dutifully clunks away in response. Cornier than a Kellogg’s Corn Flake (floating in its bowl taking movies). Streisand’s rolled-eyes pass through the Beatles’ “Honey Pie” is what the English called “taking the piss.” On the other hand, and with reservations about its spoken outro, her version of the Beatles’ “Goodnight” is a stately recontextualization.

I hear contempt in performances such as “Honey Pie”; others condescendingly hear confusion. Today, most of us are so acclimated to the lyric-writing innovations sparked by Dylan, we forget—unless a Nobel Prize reignites clueless hostility—how ridiculous these innovations sounded to some in the sixties: not a blend of blues couplets, Symbolism, Tin Pan Alley, sound-over-sense serendipity, Bible jokes, and evocative abstraction but rather druggy dropout craftless nonsense, not poetry but charlatanry. Streisand didn’t bother with Dylan, but she got to many songwriters who followed in his wake, and as someone who relied on narrative and characterization to pursue her style, and who was more interested in detailed dramas of the imagination than in introspection, she would have reason to see Clive Davis’s modernization mandate as a misunderstanding of her art, even a philistine one. You can change for money, but it’s usually better to change for love, even if you’re quietly thinking of money too. Miles Davis, another key Columbia artist, was in the late sixties both adapting and innovating, following and leading, calculating and creating, watching James Brown and Sly Stone but also the horizon. Though probably Streisand did already admire those young songwriters—her sincere admiration would soon be clear—she hadn’t yet found young artists and collaborators who could make the shift in repertoire feel like her initiative.

In three sessions starting in the fall of ’69 and wrapping up in the spring of ’70, Streisand tracked eight songs with Gold and Matz for an album to be called The Singer. It would be made up of new nonrock material by pros born in the midtwenties through the early thirties: the Legrand-Bergman axis; Martin Charnin, a theater vet who later hit big with Annie; Ron Miller, who’d cowritten hits for Stevie Wonder, including “For Once in My Life.” Davis, feeling these sessions were too tentatively modernizing, asked Streisand to back-burner The Singer and instead try working with producer Richard Perry. A good choice, Perry was a Streisand contemporary who would soon be famous for his work with Fanny, Ringo Starr, Harry Nilsson, Carly Simon, and Rod Stewart. Before Streisand, he wasn’t a known money-maker. Presumably, his Captain Beefheart credit didn’t get him the Streisand gig. But he had overseen Fats Domino’s unfazed renditions of “Lady Madonna” and “Lovely Rita” from Fats Is Back, so maybe he’d suggest pop tunes Streisand would cotton to.

The resulting album, 1971’s Stoney End, followed the previous year’s hit title song and was made with heavy session players finally credited on the jacket. The songbook is drawn from the newly classified singer-songwriters, plus Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, who stayed behind the scenes while some of their Brill Building–era peers took the spotlight. Every song is a good one, and most sit well with Streisand.

Unfortunately, the album starts with one of those mismatches. During Streisand’s stiff version of Joni Mitchell’s “I Don’t Know Where I Stand,” we miss Mitchell’s voice, her guitar, and, frankly, her melody. Compared to the folk-formed and artier Judy Collins, who with Aretha Franklin, Dusty Springfield, and eventually Joe Cocker and Rod Stewart represented the elite of contemporary interpreters of prestige pop, Streisand seems adrift. Perry wisely brings in Randy Newman to play piano on his two Stoney End songs, “Let Me Go” and “I’ll Be Home,” and Streisand is in sync with Newman’s refracted blues and wit and melancholy. In another sign of Perry’s wisdom, he brought in Gene Page, who had arranged the Righteous Brothers’ “You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feeling” and would become one of the most visible R&B and pop arrangers of the seventies through his work with Marvin Gaye, Barry White, Elton John, and others.

Streisand is clearly inspired by Page, and by three tunes from Laura Nyro, then still in her early twenties and at the peak of her eccentric powers. Nyro crafted R&B-rooted art pop whose rangy melodies featured intervallic leaps often challenging Nyro’s own fearlessly employed upper register. The style gave Streisand opportunities to have fun with her top notes and her improvisational flair during builds and crescendos, as on the ecstatic last minute of the titular song. Page’s arrangements of Nyro sand off edges, especially from “Time and Love,” and at times he hews too closely to the originals. But they flow nicely, and Streisand’s commanding vocals shut down suggestions of redundancy. A final highlight is Streisand’s enveloping version of Carole King’s “No Easy Way Down,” which doesn’t depart much from King’s but is all the same equally essential. The backing vocals by a large cast including Clydie King and Merry Clayton are models of the art. On blues, Streisand has sometimes been too much the try-hard, but she’s a natural, inventive soul singer. This talent, first explored on Stoney End, was one of the great revelations of her seventies and early eighties work.

The changed repertoire, in addition to imposing aesthetic and procedural adjustments, exposed Streisand to new strains of unwelcome comparison. Barbra Joan Streisand, a second Perry production released in August of ’71, swaps Stoney End’s Nyro trio for three songs by Carole King. A smart idea, given Streisand’s treatment of “No Easy Way Down” and King’s track record as a writer. King’s first (and second-best) solo album, 1970’s Carole King: Writer, didn’t yield hits, and she hadn’t charted as a performer since 1962’s excellent forty-five “It Might as Well Rain Until September.” So when Streisand and Perry cut King’s “Beautiful,” “Where You Lead,” and “You’ve Got a Friend” for BJS, they couldn’t have known Tapestry would become an genre-defining smash, or that James Taylor’s “You’ve Got a Friend” would go No. 1 that summer. With Nyro, redundancy threatened but was fought off. Here, Streisand’s versions look a bit like knockoff scarves languishing on a street vendor’s blanket. Given that King and Taylor had mastered the studio-as-living-room approach crucial to the era’s demand for beaded intimacy, Streisand’s “Beautiful,” arranged by Nick De Caro, feels overdressed, more like studio-as-Vegas-ballroom. But take another look at “Where You Lead,” a great rock ’n’ roll performance, more galvanizing than the original, thanks in large part to arranging and backing by an augmented Fanny, whose albums were also produced by Perry. Fanny also sets the stage for “Space Cowboy.” These tracks were the first and, I think, the only time Streisand recorded with a working rock band.

More of that would have bested a version of John Lennon’s fragile “Love” with its drippiness unclouded, or “The Summer Knows,” an oft-recorded horror with music by Legrand and lyrics by the Bergmans. I recoil at every minor arpeggio, every descending bass line, every maudlin lyric, every dramatic whisper. “I Mean to Shine,” the only song Donald Fagen and Walter Becker managed to place during their brief pre–Steely Dan days as song hawkers, shows the writers suppressing their voice as if lunch depended on it, but some seeps through. Fagen, like Newman before him, is invited in to play piano, so we have a single track featuring, among other notables, June Millington, Hugh McCracken, Alice de Buhr, Donald Fagen, Bobby Keyes, and Barbra Streisand. Cool band!

The album, an odd patchwork, includes two of Streisand’s high-water marks. One, superficially incongruous, is “Mother,” John Lennon’s spare but monumental song of parental abandonment, written during his period of therapy with Arthur Janov. Lennon, whose father left home for good during Lennon’s infancy and whose mother died when Lennon was seventeen, intensifies his original by demonstrating Janov’s primal scream therapy. Streisand, whose father, you’ll remember, died in her infancy and whose mother reportedly didn’t quite understand her, replaces the screaming with belting, a well-timed modulation, and coloratura passages including impressive portamento. She makes a powerful connection between the Munchian catharsis Lennon was after and the catharsis Streisand achieves through stage-derived bravura, the sheer force of her voice, its power to inhabit the listener’s body and reveal more than we thought possible from ourselves or the world. “Mother,” like her later recording of Rupert Holmes’s less fertile “My Father’s Song,” is autobiographically enriched, but that’s unusual in Streisand’s body of work. Most of the time, listening to Streisand is about her voice, about her decisions, but it’s about our self-expression, our emotional discharge.

To hear a single track demonstrating much of Streisand’s range and how intelligently she employs it, turn to her BJS version of Buddy Johnson’s “Since I Fell for You,” which briefly (if somewhat opaquely) slides down to E3 (the E below middle C) and climaxes at G5 (a perfect twelfth—that is, an octave and a fifth—above middle C). With another very good yet unobtrusive Gene Page arrangement behind her, Streisand makes unerring choices bar to bar. The song is performed in C major, the people’s key, but most of us won’t be able to sing it like this. A few things you might listen for: In the introductory verse, the long note—a whole note tied to an eighth—on the second syllable of “depart”; the rich tintinnabulation of “You” at the top of the first A section; the blues slur moving from E-flat down to D on the word “now” in that same A; the melisma that brings her down to E3 in the next bar; the legato “Love” on the first bar of the second A section; the switch to belting in the third bar of the bridge; the talky, vocal-fry resignation on “you loved me” a few bars later; the repeated “I’m still” as the bridge finishes; the sustained, spine-tingling G at the start of the final verse and the grace note she uses to get out of it; the octave when “every” ascends to “night” as we approach the last refrain; and how pensively she delivers the major seventh, B natural, and the C that follows it in the penultimate refrain. What must it feel like to sing like this?

The premature Live Concert at the Forum, from 1972, includes a rarity: bad Streisand vocal performances, such as the consistently out of tune “Stoney End.” Fifteen-album record deals encourage the overproduction of albums.

After this came the often-censured Barbra Streisand … and Other Musical Instruments. Strangely, it is both a companion to another TV special and Streisand’s most experimental album. The experimentation is sometimes jokey and backdated, but the album’s interest in juxtaposition is sincere, the results beguiling. The album’s 100-plus musicians come from around the globe: there’s a symphonic orchestra as well as specialists in traditional and classical African, Indian, Japanese, Native American, Turkish-Armenian, Spanish, and Irish music. There’s a lilting raga-influenced medley (not an ordinary medley!) of “Johnny One Note/One Note Samba” enriched by sitar. Another medley is accompanied by kitchen appliances. There’s a funny patter song by Lan O’Kun, “Piano Practicing,” that returns to the childhood remembrances of My Name Is Barbra. There are rejiggerings and abridgements of Streisand hits that tour global pulses through an “I Got Rhythm” leitmotif. There’s an insightful “Glad to Be Unhappy” backed by samisen and koto—all the album’s ballads are freshly beautiful not so much for their novel instrumentation but for the estranging surroundings of the whole enterprise. There’s a monologue and two semi-standards— “By Myself” and “Come Back to Me”—supported and subverted by synthesizers and effects of the type home recordists later depleted trust funds to buy and restore. Plus more Arlen/Capote, a Schubert lied with calls for a sing-along.

You might think some vanguardist manque was prodding Streisand, but TV mainstays Ken and Mitzie Welch did the arrangements, drummer and bandleader Jack Parnell (whose outfit, a few years later, would ghost for the Muppet Band) served as musical director, and Streisand’s longtime manager, Martin Erlichman, is credited with album production. It’s her.

Like producer Hal Wilner’s work on the eighties musical variety show Night Music, a late-night home for hip juxtapositions and perceptive incongruities, Barbra Streisand … and Other Instruments is kind of amazing for its music and for its mere existence, that people with money and jobs to protect agreed to finance something so capricious. I happily overrate it. Those of us who love certain superstars and the glory of pop but are also drawn to noncommercialism fall hard for mass-cult oddities such as … and Other Instruments, The Beach Boys Love You, McCartney II, or Neil Young’s Trans (and, I would hope, rust-free examples prized by younger listeners). We might even come to prefer them, sentimentally more than objectively, to the more representative and canonical albums that made the self-determined oddities possible and meaningful.

January of ’74 saw the release of two albums called The Way We Were: the soundtrack to the Streisand-Redford movie, and the studio album featuring, more or less, the late-’73 title hit, Streisand’s first No. 1, though the vocal on the album version of “The Way We Were” isn’t the one heard on the single. Nothing is ever the way it was. Shedding all-out rock and small-screen experimentalism for state-of-the-art MOR, the album revives several songs intended for the retired Singer while attenuating elements of the Perry-Page albums. Now working with producer Tommy LiPuma, Streisand includes just three pop-star compositions, all rooted in R&B. From that corner, “Something So Right,” Paul Simon’s marriage of sweet love song and witty self-reflection, is agreeable if unenlightening in Streisand’s hands. Less can be done with “Being at War with Each Other,” one of the empty message songs from Carole King’s swift decline. Streisand sings the hell out of Stevie Wonder’s “All in Love Is Fair,” but that’s the Innervisions cut I always skip if my hands aren’t full.

The Bergmans, either with Legrand or Marvin Hamlisch, dominate the rest. I understand how these florid and lugubrious songs showcase and revive Streisand’s theatrical style, and her voice, richer than ever, has been expertly recorded and mixed, right up front while still letting the band be felt. But I side with Clive Davis on the Singer holdovers, and though I admire “The Way We Were,” I’m mostly grateful that, through Gladys Knight’s cover, it helped birth Wu-Tang Clan’s “Can It Be All So Simple.”

Heeding the cries and fidgets of dyspeptic bohemians, Streisand was ready in the fall of ’74 with an album including tunes by Bob Marley, David Bowie, Buck Owens, and Bill Withers. Like a mixtape from Jefferson High’s coolest senior, but when you pop it in the deck, everything’s wrong. ButterFly was produced by Jon Peters, to whom Streisand was then romantically attached. Some argue that Peters, who had built his family’s hairdressing business into three flourishing LA salons and who met Streisand while delivering a commissioned wig to the set of For Pete’s Sake, wasn’t qualified to produce a Barbra Streisand album, I guess on the grounds that he hadn’t previously produced any recordings. Hey, you gotta start somewhere. Tom Scott, who had helped stoke the star-maker machinery for Joni Mitchell, was called in to bash out arrangements. The song selection is often (not always) hip, but rarely right. Withers’s “Grandma’s Hands” is so steeped in African American family life of the small-town South, it’s hard to puzzle out why Streisand thought it would benefit from her engagement. The Marley fumbles. Bowie, a fellow thespian, was a savvy pick, but “Life on Mars” gets in little more than a few cool vocal licks.

If The Way We Were is blandly, expertly bad, ButterFly is comically bad. When it isn’t unintentionally funny, it resembles a dinner at which you meet an old friend’s new partner and instantly root for their relationship’s failure. The chorus of the opener, “Love in the Afternoon,” goes “And deep in my soul / I could feel a quiver / Then he went down / and found that sweet old river.” On subsequent albums, Streisand would tap into a convincing and contemporary eroticism, but this isn’t it. A side note: In 2011, an LA jury ordered Peters to pay $3 million to a former assistant who had brought charges of sexual harassment.xv

ButterFly is the only Streisand solo album not to contain a photograph or illustration of the star (granted, the naïve likeness on Color Me Barbra isn’t identifiable), which may have signaled instant disownment. For her next album, Streisand recruited Rupert Holmes, the erudite singer-songwriter and utility man later famous for his 1979 page-turner, “Escape (The Piña Colada Song).” By the midseventies, quite a few pop acts, often with M names—Bette Midler, Barry Manilow, Melissa Manchester, Manhattan Transfer, the Pointer Sisters—were working with templates set by Streisand or otherwise updating prerock styles. In keeping with that trend, Lazy Afternoon, the 1975 album Streisand and Holmes put together with coproduction by Jeffrey Lesser, returns, aesthetically and procedurally, to her earlier work, especially her second and third albums. The material, however, is mostly contemporary, with Holmes contributing three of his own songs and a fourth cowritten by Streisand. As in the old days, Streisand sings live with an orchestra, with Holmes conducting his own arrangements. (There are also synths.) The title standard is a treasure from 1954’s Homeric musical The Golden Apple, by Jerome Moross and John LaTouche. Holmes’s almost synesthetic arrangement is one of the best Streisand has ever been given, and her vocal is delicate and evocative, a marvel. Streisand’s vibrato can resemble the warmest analog synthesizer, by which I mean: the other way around. “Lazy Afternoon” is one of my favorite songs to play and hear. My favorite versions are languorous version released in 1979 by Shirley Horn, and the versions by Joe Henderson, especially from Pete La Roca’s Basra and from Henderson’s Power to the People. But Streisand’s, too, is great.

Of the album’s remaining songs, only “A Child Is Born,” by the Bergmans with music by Dave Grusin, taking cues from Erik Satie, approaches the title song’s beauty. Much of it, in truth, isn’t good, but it has an integrity and coherence absent from ButterFly, and it’s a more interesting engagement with MOR and nostalgia than The Way We Were. The album’s mellow mood is interrupted by a version of the Four Tops’ “Shake Me Wake Me (When It’s Over),” unsuccessful but auspicious in showing Streisand’s early openness to disco.

There were two bicentennial releases. Depending on your loyalties, Classical Barbra, which contains short pieces from the classical vocal repertoire including lieder, chansons, and other art songs by composers such as Wolf, Debussy, and Fauré, is either admirably interloping or grossly presumptuous. As a listener, I dabble in art song but am hardly a connoisseur. That caveat issued, Classical Streisand to me sounds dilettantish but not unpleasant, and more listenable than most of the decadent rock and funk from the soundtrack to A Star Is Born. The soundtrack’s hit, “Evergreen,” is pretty, and “Queen Bee,” a Rupert Holmes novelty, enjoyably campy.

Streisand Superman, from 1977, isn’t an art move like Lazy Afternoon and doesn’t have anything as transcendent as that earlier album’s highlights. It’s fun, though, handsomely produced by Gary Klein, and stocked, for the first time in a few albums, with up-tempo numbers both driving and melodic, including disco more convincing than the Four Tops cover. Played by first-call session people (Larry Carlton, Jeff Porcaro, et al.), the album grooves more than any Streisand album since the Perry productions, though with an adult-contemporary cushion. “My Heart Belongs to Me” is the big-feelings single, “Cabin Fever” the glitzy cocaine rocker, while Roger Miller’s “Baby Me Baby” is turned into a Rhodes-drenched slow jam. Billy Joel’s “New York State of Mind” seems to call for a more relaxed approach than Streisand’s, but her reading is no blighting Robert Moses highway. Product through and through, Streisand Superman hasn’t lost its aroma of cellophane or its charm.

The following year’s Songbird assembles much of the same large and corporate team with fine but less memorable results. Annie’s “Tomorrow,” which I’d typically prefer to hear next week, sounds good gently sung by an adult in this bossa-like arrangement. The contemporary songwriters in Streisand’s late seventies stable, folks like Kim Carnes and Stephen Bishop, were operating several floors down from Laura Nyro and Randy Newman, but they gave her enough to chew on. Songbird has the original, solo version of “You Don’t Bring Me Flowers,” written by Neil Diamond with the Bergmans. The song reaches its lachrymal apotheosis in the frequently anthologized duet with Diamond, first suggested by a radio PD’s prototype edit of Streisand and Diamond’s respective solo versions. Streisand and Diamond, acquainted since their school days, are so good together, I can hardly bear it. A cheesy but genuinely painful song of divorce, and thus one of the quintessential seventies works of art.

Wet, Streisand’s last solo effort of the decade, is a concept album about water. Tears, baths, cataracts, rain, a lot of rain. It’s an occasion for compromise: Streisand, for instance, can dress Arlen and Mercer’s “Come Rain or Come Shine” in a light funk mackintosh. The hit was the duet with Donna Summer, “No More Tears (Enough Is Enough.” I like the album fine, but I tend to wear galoshes.

°

We talked earlier about transparency versus assertion. Barry Gibb, who produced Streisand’s 1980 album, Guilty, was, like, for instance, Gamble and Huff before him and Prince after, an assertive producer. He didn’t help you realize your vision, he fit you into his. Gibb, who as with Holmes had been recruited by Streisand, wrote all the Guilty songs, one alone and the rest either with his brothers or the backstage Bee Gee Albhy Galuten. He then recorded the tracks with coproducers Galuten and Karl Richardson and some of the period’s best soft rock, R&B, and fusion session players, including drummer Steve Gadd, keyboardist Richard Tee, guitarists Cornell Dupree and Lee Ritenour, bassist Harold Cowart, and others, plus lots of fat synth patches.

The players get to stretch out. Several of Streisand’s seventies records groove but none are as billowy and pocketed as this one. “Promises” must be danced to and has that intoxicating quality, found on much of the best disco, of dancing through pain. Streisand overdubbed her vocals, and Gibb’s unmistakable vibrato and falsetto are all over the record in two duets and in layered harmonies. (The album has more harmonized choruses, assisted by Gibb and session vocalists, than any previous Streisand album.) That Guilty is Streisand’s biggest-selling album would seem to repudiate of her ethos of independence; it’s rather like a Bee Gees side project on which she stars. Previously, she had let songwriters form pluralities on her albums, and had made albums in close partnership with producers or arrangers (particularly Matz, Legrand, Perry, and Holmes), but this was the first time she had turned over so much control over an album.

But if it accordingly can’t be her magnum opus, it is one of her great vocal performances, tempered without abandoning her stock in trade, stylized as ever but not self-referential, which is always a danger when singers reach career midpoints. Water coheres when it’s cold, so I suppose this is only her most cohesive album since the last one, but it flows better than any of her albums.

Gibb and his collaborators are melodists and harmonists first, not clever, literary types, and though they had written story songs before, on Guilty they write of love requited, love ending, love lost, love pined for. I’ve heard the album a hundred times but can’t always remember which romantic stage each song is documenting. Instead I passingly notice a cliché (“I’m just an empty shell”), a good detail (“but your throat is kind of dry”), an ingenious background-vocal response (“It oughtta be illegal”). It works because everything is earnest, melodramatic, sometimes dark and desperate, Gibb’s vocal quiver a sign of desperation; the lyrics provide the foundation Streisand needs to insert story and emote. The convenience of love songs is that they don’t oblige exposition. And the melodies and harmonies are simply richer than most of what Streisand had recently been given: harmonies blending fancy R&B and pop—Motown, Beatles, Philadelphia International, Bacharach-David, Left Banke—and providing interesting modulations always in service to pop pleasure, dark melodies that stall their major releases. Streisand sounds ethereal through much of the record, but when she wails, as on “Make It Like a Memory,” there’s something to wail about, even if it’s vague and inarticulate. That song’s desideratum to me always seems doubly rich in pathos because, as I wrote elsewhere when trying to deal with this album in fiction, what’s worse than a painful memory? Despite its sexy album cover, Guilty isn’t explicit about the boids and the bees, but because the music is so lithe, relaxed, and pleasurable, it’s Streisand’s most erotic album. The production is adamant that funk can be padded; even the whip credited to Joe Lala on “Life Story” has no more crack than the snare. But like the album, it’s still a whip.

Memories, a 1981 collection, sucked in completists with two new songs, “Comin’ in and Out of Your Life,” and Streisand’s minor hit version of Andrew Lloyd Weber and Trevor Nunn’s “Memory.” I have found ways to surrender to this song without loss of dignity. During the early eighties, Streisand was most engaged in cowriting, then directing, coproducing, and starring in Yentl, the 1983 feminist adaptation of an Isaac Bashevis Singer play and story to which Streisand had secured the rights back in 1969. Its songs, composed by Legrand with lyrics by the Bergmans, include the affecting “Papa, Can You Hear Me?” Most are better heard in the film, and even there they can drag.