More Herself

Abbey Lincoln and her songs

Abbey Lincoln’s work as a musician, writer, activist, and actor bears on multiple histories: of jazz and the music’s underacknowledged singer-composers; of film and theater; of Black liberation movements and feminism, though, it’s true, Lincoln didn’t herself identify as a feminist. It benefits from the sort of panoptic criticism practiced by the writer and multidisciplinary artist Harmony Holiday, who’s working on a biography of Lincoln and has written about the singer and songwriter for the Poetry Foundation and in essays posted on her newsletter, Black Music and Black Muses. Over the past week, I reread or discovered other excellent pieces on Lincoln, a few of which I’ll quote from below. Carol Friedman’s forthcoming documentary, the long-in-the-making Abbey Lincoln: the Music Is the Magic, should further enrich the record. What follows is comparatively narrow, a fan’s digressive overview with an eventual focus on Lincoln’s self-penned songs. The first of these songs appeared on 1959’s Abbey Is Blue, an album of expansive emotional imagination and coiled anger, a jazz masterpiece in a year swarming with them. Lincoln’s later songs—wise, idiosyncratic, easeful—defined her resurgence from the start of the nineties until near her death in 2010.

She was born Anna Marie Woolridge in 1930, the tenth of twelve in her family, and spent early days in Chicago but was mostly raised in Michigan. She went to high school in Kalamazoo but before that the family lived on a farm in Cass County’s Calvin Township, which had a Black population going back to the middle nineteenth century and, in the antebellum period, a strong abolitionist community. As a girl, Lincoln taught herself to play songs on the family piano. In a photo reproduced in the CD booklet from her 1992 album, Devil’s Got Your Tongue, eight of the Woolridge children and their parents, Alexander and Evalina, pose in front of this piano, a tall upright. On that same album she pays separate tribute to her parents, revealing her depth of feeling and wide field of vision. “Evalina Coffey (the Legend of),” whose first solo is by the trombone hero J. J. Johnson, is Afrofuturist chamber blues and gossamer Tin Pan swing about a woman who travelled to St. Louis by spaceship. “Story of My Father,” sung with the Staple Singers, is questioning gospel whose first question is, “Do we kill ourselves on purpose?” As a teenager Lincoln learned from records by Billie Holiday and Coleman Hawkins, the first a lifelong polestar, the second a future collaborator. She started her professional career in the early fifties, gigging in Los Angeles and Honolulu, and was rechristened for the stage by her first manager, Bob Russell. Best known as a songwriter, Russell wrote the lyrics to Duke Ellington’s “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore” and “Do Nothin’ Till Yor Hear from Me” and with Carl Sigman wrote “Crazy He Calls Me.” He’s also partly responsible for the Hollies’ “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother.” He positioned Lincoln for the “svelte, chic world of the supper club,” as she put it in a 1986 interview with Terry Gross. Image references were Lena Horne, Dorothy Dandridge, Eartha Kitt, Julie London. Russell wrote some of the music for The Girl Can’t Help It, Frank Tashlin’s unfunny 1956 comedy starring Jayne Mansfield. The movie is best remembered for its pantomimed but incendiary performances by Little Richard, Eddie Cochran, and others, but Lincoln’s there, too, performing up-tempo mock-gospel in a hugging orange-chiffon gown designed by William Travilla and previously worn by Marilyn Monroe. “They were creating some rep for me as some breasty sexy woman,” Lincoln told Amiri Baraka, one of her critical champions. She admired Russell’s music but resented the act. “I can’t stand some man looking at me and just thinking about sex.”

In 1957, Liberty released the singer’s debut album, Abbey Lincoln’s Affair … a Story of a Girl in Love. Not a title Chekhov would have approved. It includes five songs written or cowritten by Russell and is sequenced with hopes of charting a romance from flirtation through dissolution, much like Joni Mitchell’s great 2000 album, Both Sides Now, a blend of standards and refashioned Mitchell songs laid out with the same narrative aim. Affair’s beige arrangements are by Marty Paich, Benny Carter, and Jack Montrose. Later, Lincoln would remember her mostly unrecorded early work as the unpopped kernels of a pre-Enlightenment period before she had an artistic vision, the autonomy to realize it, or a collaborative community. To enjoy the album even a little is to feel disloyal to Lincoln’s story, an escalator of self-actualization. But to read the liner notes from Lincoln’s subsequent albums, and the echo-chamber accounts of her trajectory, is to be reminded of the bullying knee-jerk animus some tastemakers have had toward all but a few pop singers, women in particular. And so I want to defend her work’s prelude, a little. On Affair, she isn’t yet a distinctive stylist, and her caution or it might be indifference helps stymie a concept already doomed by the arrangements and some of the tunes. But she doesn’t sound artificial. Sometimes you don’t mean it, but the thing you do mean beams through a tiny window, reflects off a spool of thread, and lavenders a nickel-sized spot on the floor. Or it doesn’t matter if the singer means it, so long as the listener does. I like Lincoln’s version of Magidson and Wrubel’s “The Masquerade Is Over,” though I’ve never liked the song’s bridge. Maybe at the recording sessions that’s the song she most felt, the one about faking it. “I’m afraid the masquerade is over,” she sings, and I think, Are you sure? Lincoln was able, Harmony Holiday writes, “to wear a mask of mirrors, so that those who watch and listen to her are forced back into their own subjectivity, forced toward the self-reflexive vulnerability that spectators usually seek to avoid.”

Around the time Affair came out, Lincoln moved to New York and was made over by a new milieu: intellectual, experimental, radical, Afrocentric. At the center of her circle was Max Roach, whom she credited, along with his colleagues at the forefront of jazz, with magnifying her knowledge of music and igniting her commitment to it as a means of personal and political expression. Lincoln and Roach became romantic as well as artistic partners and were married from 1962 to 1970. Roach was six years Lincoln’s senior and among music’s seers: he was one of the principal architects of modern drumming; he had led, with Clifford Brown, the preeminent small group of the midfifties before Brown’s death in a car accident; he had expanded the music’s metrical landscape with recordings such as Jazz in 3/4 Time; he was about to join his music more explicitly to political action. Lincoln, though still uncovering her voice when the two met, entered the relationship with an impressive if regretted resume of her own and had achieved a measure of celebrity. She’d been in Ebony, in Jet; she’d been singing since childhood and had studied great singers. So while Roach’s influence on her must have comprised mentorship (she has said so), we might see him, too, as an inspiring, close-at-hand vanguardist from a new scene, prodding Lincoln toward risk-taking as Yoko Ono later would with John Lennon, or Kathleen Brennan with Tom Waits. The partnerships, obviously, are only distantly analogous; Lennon and Waits were famous men, the first even more famous than … well, you know the line. But there might be echoes.

Shortly after the release of Affair, Lincoln parted ways with Russell and accepted Roach’s challenge to make a jazz album. Riverside’s Orrin Keepnews was receptive, and the result was That’s Him! It’s her second 1957 concept album, impressive and oppressive, made up of songs sung by women to men, some of cheery devotion, some of resigned devotion through subjugation. Two are associated with Billie Holiday: Holiday’s own “Don’t Explain,” and “My Man (Mon Homme),” the French song by Maurice Yvain, Albert Willemetz, and Jacques Charles later given English lyrics by Channing Pollock. In France, “Mon Homme” was published in 1920 and a hit for the chansonnier Mistinguett. It became her signature song. I’m partial to her commanding 1938 version, cut when she was in her midsixties. Willemetz and Charles’s French lyrics were drawn from a play by Francis Carco and André Picard and perhaps further inspired by a complicated love quadrangle glossed in John Szwed’s Billie Holiday: The Musician and the Myth. Pollock’s translation was popularized in the States a year later by Fanny Brice, the path-breaking singer and comedian who inspired Funny Girl. Brice, going through heartache of her own, sings the song assertively, with a ruefulness not untouched by comedy. It became her signature song. To again abandon linearity, Barbra Streisand’s bravura version starts in tears and ends in belted triumph, but the ambiguity of that transition is easier for modern audiences to follow because the song’s most disturbing English lyric, originally written as a kind of aside—“he isn’t true / he beats me, too / what can I do?”—has been elided. Those lines are absent, too, from Holiday’s sprightly 1937 version for Brunswick, whose verse isn’t the one known from Brice. Holiday did two takes of the song for Decca on December 10 of 1948. The first, the alternate, is twelve seconds longer. Twelve more things happen. She and a quartet take it as if they’re underwater, and she sinks into the song’s despair with her unrivaled conversational acuity, restoring the verse from Brice’s hit, elongating the descent of the above-quoted lyric. When, for the chorus, the song shrugs off its shroud, moving from F-minor to its relative major, she brightens her tone and the feel purrs to gentle swing. Patting your foot is either complicity or empathy, which is Holiday’s challenge. Lincoln’s interpretation follows Holiday’s but brings the song back to the theater. “He’s not much on looks,” she sings, “he’s no …”—and during this fermata the reverb has ballooned—“hero out of books,” after which Paul Chambers’s arco bass adds a bookmark that started out as a lunch receipt. When the chorus comes around, it’s for slow dancing too close. Soon, Lincoln would steer clear of such narrators, “this masochistic woman who tells all,” as she put it, not too sensitively, in that 1986 interview with Gross.

The That’s Him! band—Kenny Dorham, Sonny Rollins, Wynton Kelly, Chambers, and Roach—is peerless. Hush, now, and listen to Dorham’s and Rollins’s solos on “Don’t Explain.” The casually assured arrangements evoke the second set. The highlight, however, is a cappella, an understated dramatization of Phil Moore’s “Tender as a Rose.” Solos are reined in on the following year’s It’s Magic, half of which is done with an octet playing Benny Golson’s arrangements, half with a quintet mostly playing as they like. Golson’s genius notwithstanding, his charts can feel mismatched to Lincoln, who seems stoked by more open forms, though everyone is in step for “Just for Me,” a modest tune by Jimmy Komack. Lincoln brings across every dry joke with a soft sell. Singing is also acting, and though before long Lincoln will famously scream, she’s also adept at expressive little effects picked up by microphones of the sort that need to be suspended from protective nests. Her work is seriocomic, as serious as can be and also very funny. Someday you should come over, and I’ll play you her “If I Only Had a Brain,” from 1998, how she delivers individdle. Ray Bolger’s work is also seriocomic. When she gets to, “With the thoughts I’d be thinkin’ / I could be another Lincoln,” she doesn’t italicize the pun. But she could.

The third album’s Holiday tribute is an escalator-paced “Ain’t Nobody’s Business.” The album closes with “Little Niles,” Randy Weston’s waltz for his son, heard here with Jon Hendricks’s lyric. Weston’s several recordings of the song cover a rainbow of moods and include later versions, such as the raucous one on Tanjah, cut with the tune’s grown-up namesake, then Azzedin Weston, on conga. Lincoln’s interpretation is pensive, her approach guided by Hendricks’s line “And silently you wish time would slow up / so he’d never grow up.” During an improvisational chorus, she gracefully moves through vowel sounds, trading eights with trumpeter Art Farmer, then with Golson.

For Abbey Is Blue, her last album for Riverside and her first triumph, Lincoln worked closely with producers Keepnews and Bill Grauer in choosing repertoire. From here through the rest of her career, especially as a writer, she would minimize songs of romantic life—they’re present, but she tends not to use the shorthand and backdrop of romantic relationships. A lot of these love songs, you know—that’s not what they’re about, that’s how they’re about. But you can get to that stuff by another route, you can get through that stuff by another route. The narrators on Abbey Is Blue are often lonely, but their answer isn’t necessarily a mate.

The album’s sequencing is novelistic, its bookends ingenious. The heart of Blue is probing, expressive, and languid, but it opens with the undulating “Afro-Blue,” whose sadness is obstructed, and closes with the uplifting “Long as You’re Living,” a short expression of carpe-diem optimism with sack-suit unison lines and a fitted 5/4 groove. Roach knows his way around 5/4. The pianoless quintet is completed by bassist Bobby Boswell and three horns: Tommy and Stanley Turrentine, and Julian Priester. Both of these bookending songs have lyrics by Renaissance man Oscar Brown Jr., who like Hendricks had a gift for writing words to popular instrumentals. Besides Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro-Blue,” a minor blues laid over a cross-rhythm, he did Nat Adderley “Work Song” and Bobby Timmons’s “Dat Dere.” In Brown’s lyric, “Afro-Blue” is an erotic dream of observation or voyeurism, and of returning to a homeland, Africa or perhaps Cuba, where Santamaria was from. The singer is alone in a crowded place of her imagination, and then, on the very slow next song, “Lonely House,” from Kurt Weill and Langston Hughes’s Street Scene, she’s cloistered in a bustling neighborhood. “The night for me is not romantic,” Lincoln sings, ticking seven lonesome D’s before moving up a step from which she can reach Hughes’s brilliant verb, “unlock the stars and take them down.” Unlock them! “I get lonesome sometimes,” Elvis Presley said. “I get lonesome right in the middle of a crowd.” Brown wrote both music and lyrics for the album’s “Brother, Where Are You?” whose chorus brings Lincoln to C5 (the C above middle C), one of her sweetest notes. She sings on the album with new spontaneity, conviction, and character. She’s both a let-it-out singer and a hold-it-in singer, mingling, in Nate Chinen’s words, “bold projection and expressive restraint.”

Side two starts with “Laugh, Clown, Laugh,” an oldie Lincoln helped revive. Pagliacci for me is most effective as image except when Smokey Robinson dances him on “The Tears of a Clown.” Lincoln’s sad-clown song, kind of her second if you include “The Masquerade Is Over,” begins with jocular pathos before dropping the tempo toward sincerity. On the performance, you’ll hear Lincoln bend and flatten notes—that’ll become a big part of her technique—and otherwise play with pitch and microtones, mixing sweet, sour, and savory. And although she’s a flexible and technically advanced singer, you’ll hear some unintentionally flat notes. You’ll hear them more frequently in her later work. Voices are part of our body, it turns out. They crack like plaster, but the lines are rivers on that map under the passenger seat. They shrink like jeans, but that’s how they fit. One of the stupid cruelties of our time is the part where your friend posts a phone-recorded YouTube of Jon Bon Jovi gray and out of tune, and seventy commenters start laughing. Anyway, in this regard, Abbey Lincoln isn’t Ella Fitzgerald, or Melodyne, and some critics have been eager to blow the whistle on her inconsistent intonation. It’s no crime to note this aspect of Lincoln’s sound—kind of weird not to—but the complaints can seem small-minded, like pointing out a syntactical infelicity in a love letter. Well, everyone hears things differently. In the interest of diplomacy, I’ll admit I’m not as sensitive to pitch as some.

Hanging tough with the connoisseur songs chosen for Abbey Is Blue is Lincoln’s first recorded original, “Let Up,” a long C-minor blues on which the band is deep and reserved and Lincoln’s every instinct of tone, time, and tale is correct. For much of her work, she favors slow and relaxed tempos, and her phrasing outlines a wide beat. It’s easy to do, like signing your name on a grape. “How much more can a body abide?” she sings. The rhyme goes, “Who’s on my side?” The album isn’t packaged with a political message, and its rage is checked, but of course it’s a protest record, and a religious record of faith and doubt on which “Come Sunday,” Ellington’s weary prayer, is jostled by Weill and Anderson’s “Lost in the Stars,” whose singer wonders if “maybe God’s gone away.” It’s set in a world, to paraphrase a few more lyrics, where everyone talks of brotherhood but few mean it, where you’re blamed for what you’ve been named. “The world is going wrong,” Walter Vinson sang with the Mississippi Sheiks in 1932. “The world is falling down,” Abbey Lincoln sang in 1990, “hold my hand, hold my hand, hold my hand.”

The album was made over a few sessions with different groups. The backing can be spare, the vocal exposed and intimate. It opens your ears. Before its chorus, all we hear on “Lonely House” is a cross-stick quarter note, bassist Sam Jones pedaling footballs, Lincoln singing the steady verse melody, and a tear-slicked eyelash landing on a pajama button. On the album, Lincoln’s voice is so out front, you’ll notice tiny details of microphonics and production, many, I imagine, related to Lincoln’s proximity to the mike, but there must also be deliberate engineering adjustments, and certainly the faders are being inched up and down. I love how the color of the reverb changes during the fadeout of “Let Up.”

One of Roach’s 1958 albums was named Deeds, Not Words. He and Lincoln became increasingly active in the freedom movement, more and more antiestablishment in their art. In 1960, Roach and Charles Mingus staged an alternative festival running alongside George Wien’s Newport Jazz, drawing attention to pay inequities between Black and white artists. Lincoln, along with folk singer Odetta, dancer Ruth Beckford, and some other artists, was among the prominent Black women of the late fifties and early sixties to star wearing their hair natural and took flack for it. (“The beauticians thought I was going to ruin their business.”) In 1959, Roach and the lyricist Brown started work on a commission to be performed in ’63, marking the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation. As Michael Reagan explains in a piece for the Boston Review, the collaboration grew contentious, with Roach favoring a more radical approach than Brown’s. (For a fuller account, Reagan directs us to Ingrid Monson’s Freedom Sounds: Civil Rights Calls Out to Jazz and Africa.) On top of that friction, the situation on the ground called for a more exigent premiere, and Roach used some the pieces he and Brown had written, and new ones, to form We Insist! Freedom Now Suite, released in 1960 by Candid Records, a Cadence subsidiary run, in its short but important first iteration, by writer Nat Hentoff, a Lincoln skeptic turned champion.

The players were Lincoln, trumpeter Booker Little, trombonist Priester, tenor saxophonists Walter Benton and Coleman Hawkins himself, bassist James Schenck, conga player Michael Babatunde Olatunji, and percussionists Ray Mantilla and Thomás DuVall. The history and testimonial, then, was, multigenerational. Hawkins was fifty-five; Booker Little, who the next year would die of complications from uremia, was only twenty-one. A civil rights landmark without an expiration date, the suite addresses American racism and brutality past and present and connects it to Apartheid South Africa, where the Sharpeville massacre had taken place months before the recording session. The opening piece, “Driva’ Man,” returns to slavery days. The free-time introduction is just Lincoln with responses from her own tambourine. The words, told from an enslaved person’s vantage, tell of the drivers, who were enslaved men charged with bossing field work, and of the patrollers, the armed police force preventing, among things, people from leaving the plantation, for instance just to visit a family member without a pass. When the band enters, the time is 5/4, and to mark the downbeat Roach includes in our minds the sound of a whip. During Hawkins’s great solo, there’s a little squeak, the sort of mote often covered by a tape edit. “Don’t splice,” Hawkins counseled. “When it’s all perfect, especially in a piece like this, something’s very wrong.” The suite was Roach’s work, Lincoln would always say, but you can hear how it was realized through her fearlessness and her timbral, histrionic, and emotional scope. The centerpiece is “Triptych: Prayer/Protest/Peace,” duets for Roach’s drums and Lincoln’s wordless vocals. On “Prayer,” she sings ooh and eeh sounds in C with stately feeling. The duo transitions with a jolt to “Protest,” for which Roach’s fire drumming undergirds Lincoln’s screams: shattering, cathartic screams, unprecedented and unmatched. Farah Jasmine Griffin’s 2001 book, If You Can’t Be Free, Be a Mystery: In Seach of Billie Holiday, devotes its final chapter to Lincoln. On “Protest” she writes: “In the scream I can hear the beaten slave woman, the mourning black wife or mother, the victim of domestic abuse and the rage and anger of contemporary black Americans.” And Fred Moten, writing that on “Protest” Lincoln moves “toward a location that is remote from—if not in excess of or inaccessible to—words.”

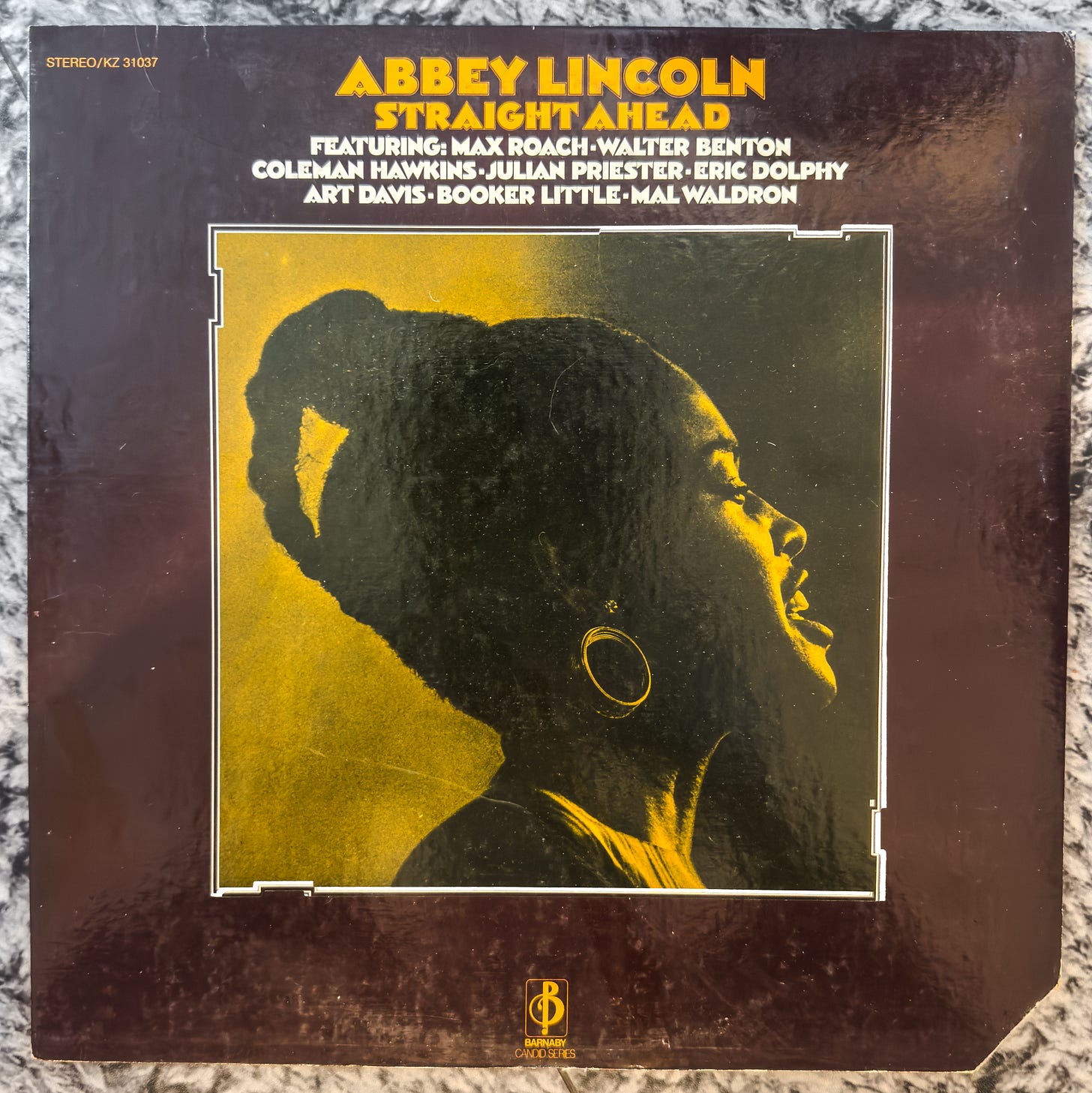

Straight Ahead, from ’61, followed We Insist! on Candid. Several of the suite’s players return: Hawkins, Benton, Little, Priester, and Roach, who acted as musical director, though arranging duties were passed around. Eric Dolphy joins on reeds, Art Davis takes over on bass, and this time there’s a pianist, Mal Waldron, who in addition to his own maverick work as a composer and leader had been Billie Holiday’s last regular accompanist. Lincoln had a hand in writing four of the album’s seven compositions. Though Abbey Is Blue isn’t by any stretch a compromising record, it is a conventionally beautiful and tuneful one. Its singer/speaker moves from her own voice to the voices of characters from finely crafted fictions, and back again, and the album’s protests could be reconciled with a gradualist path. Straight Ahead is more radical, buttonholing, individualistic, dissonant, and insistent. “There won’t be no peace of mind,” Lincoln sings on “In the Red,” a barbed dirge of penury she wrote with Roach and Chips Bayan, “until I see better days.” Not everyone was on board. A year earlier, Don DeMichael, writing about We Insist! for Down Beat, submitted an awe-struck rave, but when Straight Ahead came through the mail, Ira Gitler, a name critic and one of the magazine’s editors, wrote an infamously racist and revanchist dismissal, leading Down Beat to run a two-part transcription of a symposium, “Racial Prejudice in Jazz,” in which Lincoln, Roach, Gitler, and others participated.

Lincoln wrote the title song’s lyrics with fellow singer Earl Baker to Waldron’s music; its metaphors are effectively mixed. She wrote the adamantine “Retribution” with Priester, who takes an excellent solo. Thelonious Monk, who observed some of the session, is honored by the words Lincoln gives to “Blue Monk.” Her lyric is an early entry in her book of wisdom literature: “Life is a school / ’Less you’re a fool / But the learning brings you pain.” Over the five chord, she introduces the word Monkery, a kind of soul-searching, she explains in the liner notes, but maybe the word can’t be defined, only understood. Pieces not by Lincoln include “When Malindy Sings,” Brown’s adaptation of the Paul Lawrence Dunbar poem, highlighted by Little’s solo, and a wrenching “Left Alone,” the mournful ballad Waldron wrote with Holiday, though she died before she could record it. For that one, the horn arrangement is by Priester, the solo by Hawkins. This song and performance will take you over. You won’t be able to operate a vehicle or vessel.

After Straight Ahead, a lacuna in Lincoln’s discography. During the bulk of the sixties, she was active as an organizer. In 1961, she cofounded, with Maya Angelou and others, the Cultural Association of Women of African Heritage. She participated in panels and wrote plays, poems, and essays. From record labels, however, she got a “cold silence,” as she’d later remember it. Much of her prominent work in the sixties and seventies was in movies and TV. In 1964’s Nothing but a Man, an independent directed by Michael Roemer and shot in black and white by his cowriter Robert Young, Lincoln plays Josie, a small-town Alabama schoolteacher and preacher’s daughter opposite Ivan Dixon’s taciturn Duff. When they marry across class lines, Duff quits his relatively lucrative work as an itinerant railroad worker for a settled, humble life in town, but he’s blacklisted and terrorized when he refuses to comply with the obsequiousness expected by the town’s whites. It’s a drama of muted intensity marked by spare exchanges between which seconds are allowed to pass. Lincoln’s performance is rich in precise gestures and unornamented line readings.

Though she didn’t make records under her own name for most of the sixties, Lincoln contributed to other people’s. She’s on several of Roach’s recordings, such as “Lonesome Lover,” performed with a vocal choir conducted by Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson and featuring a burning solo by Clifford Jordan. With Nina Simone she wrote “Blues for Mama,” an early statement against domestic abuse powerfully performed by Simone. On Lincoln’s 1995 album, A Turtle’s Dream, she recorded her own version, retitled “Hey, Lordy Mama,” with guitar and backing vocals by Lucky Peterson. And there are live recordings from Roach’s sixties performances featuring Lincoln in front, including of the demanding Freedom Now Suite.

Ghosted in the States, Lincoln worked abroad. During her travels in Africa, she was given the name Aminata Moseka, which she sometimes used in her songwriting credits. Her return to records as a leader, 1973’s People in Me, came out on the Japanese branch of Phillips. In ’78, Inner City issued it in the US. It’s made up only of Lincoln’s compositions, collaborations, and adaptations. The jazz album as a start-to-finish showcase for the artist as singer-composer was unusual for the art form, though singers who performed their own songs were present from the start of recorded jazz. I suspect this is clear, but I’m using the word song to mean a composition of words and music, but you’re right, a song can also be instrumental, or a poem without music. Bessie Smith, Alberta Hunter, Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Billie Holiday—all were songwriters as well as interpreters. (Holiday and Arthur Herzog Jr., the team behind “Don’t Explain” and “God Bless the Child,” tell conflicting stories about the division of labor in their collaborations.) Ella Fitzgerald cowrote her breakthrough adaptation of “A-Tisket, A-Tasket,” performed with the Chick Webb Orchestra; King Pleasure, Jon Hendricks, Annie Ross, and others pioneered vocalese, setting lyrics to existing tunes and solos; Sarah Vaughan cowrote “Shulie a Bop” (it’s coolest lyric: “Roy … Haynes”); Peggy Lee’s songbook runs into the hundreds; Bob Dorough and Mose Allison set the pace for the school of piano-playing wits with talky voices; and so on, citing only a few examples preceding Lincoln’s “Let Up.” But it’s true the jazz vocal tradition has been a heavily and grandly interpretive tradition, and that some of the writers named above didn’t leave behind heaping stacks of songs. Lincoln’s work, like that of Nina Simone, Sheila Jordan, and Betty Carter, was a model or at least a precedent for prominent later singer-composers including Amina Claudine Meyers, Patrice Rushen, Bobby McFerrin, Cassandra Wilson, Carmen Lundy, Kurt Elling, Cécile McLorin Salvant, Gretchen Parlato, and lots of others.

People in Me was tracked in Tokyo in a wee-hours session to accommodate the band, three of whom—saxophonist and multi-instrumentalist Dave Liebman, drummer Al Foster, and conga player Mtume—had played earlier that night with Miles Davis. The rest of the group is bassist Kunimitsu Inaba and pianist Hiromasa Suzuki, whose 1976 album, High-Flying, has become a crate digger’s classic of funk and fusion. The opening song, “You and Me Love,” is Lincoln’s first recorded love song with her name in the writing credits. For that one she teamed with Johnny Rotella, a utility man whose songs were cut by Sinatra and Doris Day and who’s also in the sax session on Steely Dan’s “My Old School.” The track’s elegant nightclub sound harks back to That’s Him! and points to the mode of Lincoln’s autumn-years successes. Two of the album’s pieces, likely held over from earlier points during her recording drought, add words to pieces already in the world: “Living Room” is sculpted out of one of Roach’s large-scale arrangements, and the steady-building “Africa” springs from Coltrane, fun for Liebman, though he doesn’t get to go long. Much of the album, though, sounds like 1973, and the interplay is homey, collegial, spirited. Lincoln’s title track is a strutting universalist anthem inspired by her family’s diverse ancestry and reminiscent of “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.” (In ’92, she’d revive the song with help from a children’s choir; I churlishly prefer the earlier version.) On the transporting “Natas (Playmate),” she overdubs a second vocal part, both a response and something like a long nonmechanical delay. Self-overdubbed vocals were by then routine on pop and R&B records (among hundreds of examples, we can think of those multiplicities of Jonis and Marvins) but unusual in jazz. It’s possible Lincoln’s example inspired the great Betty Carter, who used self-overdubbing to beautiful effect on “You’re a Sweetheart” from her 1974 album. (On Bet-Car it was the second consecutive album called Betty Carter; to avoid confusion, it was later reissued as The Betty Carter Album.) Maybe a coincidence, but it’s fun to imagine this canyon of echoes.

Golden Lady, an Inner City album from 1981, has a sterling band: pianist Hilton Ruiz, bassist Jack Gregg, drummer Freddie Waits, trumpeter Roy Burrowes on most tracks, and Archie Shepp featured on tenor and soprano and a few supporting vocals. (Online, you might find a needle-drop stream of Painted Lady, which is a different issue of the same set; Golden Lady is the one you want.) Lincoln and Shepp are simpatico: their history of radicalism unites them biographically, as does their deep blues feeling and attuned exploration of the famous spaces between piano keys. The album starts with a triptych of its own, three “Lady” songs. The first is from Ellington, the second from Stevie Wonder, the third Lincoln’s own “Painted Lady,” a mission statement braiding pride, humor, and humility. “Sometimes I play the fool,” Lincoln sings, “sometimes the sage.” In the sage role, she leads off Side Two with the first appearance of her Buddhistic classic “Throw It Away,” of which there’s also a lush and lithe version from A Turtle’s Dream. It’s one of my favorite songs. Most of Lincoln is fairly straightforward and flexible harmonically. I enjoyed playing along with a few of her tunes, and I browsed a slim Abbey Lincoln Songbook published by Hal Leonard in 1993. Those charts didn’t always track to my ear, but I like some of their choices and am glad to have them on my shelf. There’s a very good one-pager of “Throw It Away” in New Standards: 101 Lead Sheets by Women Composers, the groundbreaking 2022 collection edited and curated by Terri Lynne Carrington. “Throw It Away,” like several Lincoln songs, works partly with blues structures but isn’t a blues. The verse is sixteen bars. Lincoln does the song in C-minor, but it opens with a G pedal. The vocal melody’s first interval is an ascending minor sixth, from G to E-flat, and then she toggles between G and top notes moving down in half steps, ending the first phrase, on the words “I live,” with a move from C down to B-natural. The harmony over the first two bars makes its way from a C-minor over G to G7, and by the fourth bar we’re on C-minor. The next four-bar system repeats those changes, measures nine through twelve move the idea up a fourth, and over the verse’s final four-bar system we resolve to C-minor. It builds a light tension as we lead to the chorus message. I especially love the words to the second verse:

There’s a hand to rock the cradle, and a hand to help us stand

With a gentle kind of motion as it moves across the land.

And the hand’s unclenched and open, gifts of life and love it brings.

So keep your hand wide open if you’re needing anything.

The chorus is aptly more open and flowing, with longer notes and a prettier melody and harmony. The refrain’s message, you may have guessed, is to be giving and at ease rather than possessive and anxious, to remember the sun will shine through your open fingers but not through your fist.

Talking to the Sun, from 1984, isn’t a favorite of mine but has excellent work by alto saxophonist Steve Coleman and an eclectic, contemporary sound, sort of M-Base avant la lettre. Regrettably, I never saw Lincoln play, but her reputation as a captivating live performer is supported by two albums, Sophisticated Abbey and Love Having You Around, drawn from a 1980 stand at San Francisco’s Keystone Korner. She and a sensitive trio are warm and loose-limbed, and the tunes are effortlessly, continuously renewed. In the Gary Giddins appreciation of Lincoln collected in Visions of Jazz, he describes how Lincoln, like only a few other performers in his experience, could create the flattering illusion of singling you out. “Sure enough,” he writes, “at intermission the first two people I spoke to mentioned, offhandedly and with unmistakable pride, that she was singing directly to them, and indeed, I had thought she was focused on me.” Some of that intimacy comes through on the Keystone sets. There are also two excellent volumes, released by Enja Records, of Abbey Sings Billie, recorded in 1987 at New York’s Universal Jazz Coalition, the nonprofit founded by Cobi Narita. In Lincoln’s version of “God Bless the Child,” the child is given all pronouns: his, her, their. I still want to believe there will be better times.

Gus Van Sant’s 1989 film, Drugstore Cowboy, features a fragile “For All We Know” by Lincoln in duo with Geri Allen. I’m not a diarist, but I guess it was that and a $5.95 reissue of Abbey Is Blue that primed me for Lincoln’s comeback, which proved to be a sustainedly fecund, acclaimed, and popular third act.

In the late eighties, the French record producer and executive Jean-Philippe Allard was charged with forming a jazz division at Polygram France. He made more of the gig than his patrons must have expected. He teamed with Polygram’s international cousins, lured jazz veterans with relatively lucrative contracts, and eventually convinced Gitanes, the cigarette makers, into sponsoring some of the label’s albums in exchange for putting a tacky logo on their front and back covers. From 1990 through 2007, Lincoln worked with Allard on ten albums, starting with The World Is Falling Down, ending with the capstone Abbey Sings Abbey. I love several of these albums start to finish and cherry-pick from others. They aren’t uniform, but except for a duet session with Hank Jones, most are made with small groups or rotating casts and tend to feature star soloists. Aside from Abbey Sings Abbey, all combine Lincoln’s songs with standards captured from fresh angles and, here and there, more contemporary material from outside writers. Her swirling “Mr. Tambourine Man” weds two of my heroes and has just made me weep. She made notable guest spots during these years, too. Her poignantly matter-of-fact “Ten Cents a Dance,” from Frank Morgan’s A Lovesome Thing, is exactly what Lorenz Hart hoped for, I’m sure of it. It weds two of my heroes and has just made me weep. Being self-expressive is often psychologically beneficial but isn’t, of course, artistically interesting in itself, not to others. Lincoln was a great performer, a craftsperson and an actor who knew how to achieve emotional effects through technical devices, but she also seemed unselfconscious and helplessly authentic, and her singularity expanded with age. “I’m still myself,” she told Terry Gross, “but I’m more myself now.” I’d like to linger with her inspired and inspiring closing decades, but my neck hurts, and now the doorbell’s ringing. I’ll close with a few words about the title song from You Gotta Pay the Band, released to much acclaim in 1991. Is this my favorite song? No, or only when I hear it.

The band is pianist Hank Jones, bassist Charlie Haden, drummer Mark Johnson, and tenor saxophonist Stan Getz, ailing. It was Getz’s last studio session. Lincoln would recycle her melodic ideas, and “You Gotta Pay the Band” resembles “The World Is Falling Down,” also a great song, though this tune cuts deeper. The changes are classic and beautiful and inexhaustible. I was young when I first heard the song. To play in clubs with my own band, I had to wear a wristband telling the bartenders not to serve me. Abbey Lincoln sang,

The moves were free and easy

As we danced across the floor.

The turns and the exchanges

Being what the music’s for.

But when the ball is over

And the revelry is done

You gotta pay the band

That played your song.

I thought, This song must be what life’s about, that everything has a cost and a consequence, just like they say, and that it’s more complicated than you’ll ever puzzle out but also kind of simple and, and that you shouldn’t feel ashamed to sometimes think it’s kind of simple, and that your voice will get burry, your heart, too, and that the world is falling down but maybe it’ll fall back up. I’m not a diarist. It wasn’t exactly like that. But close. I thought a lot of other stuff back then, most of it not true. But that time, I don’t know, lucky guess?

I am glad I stayed until the end.

Great writing about great music-and the hats…!