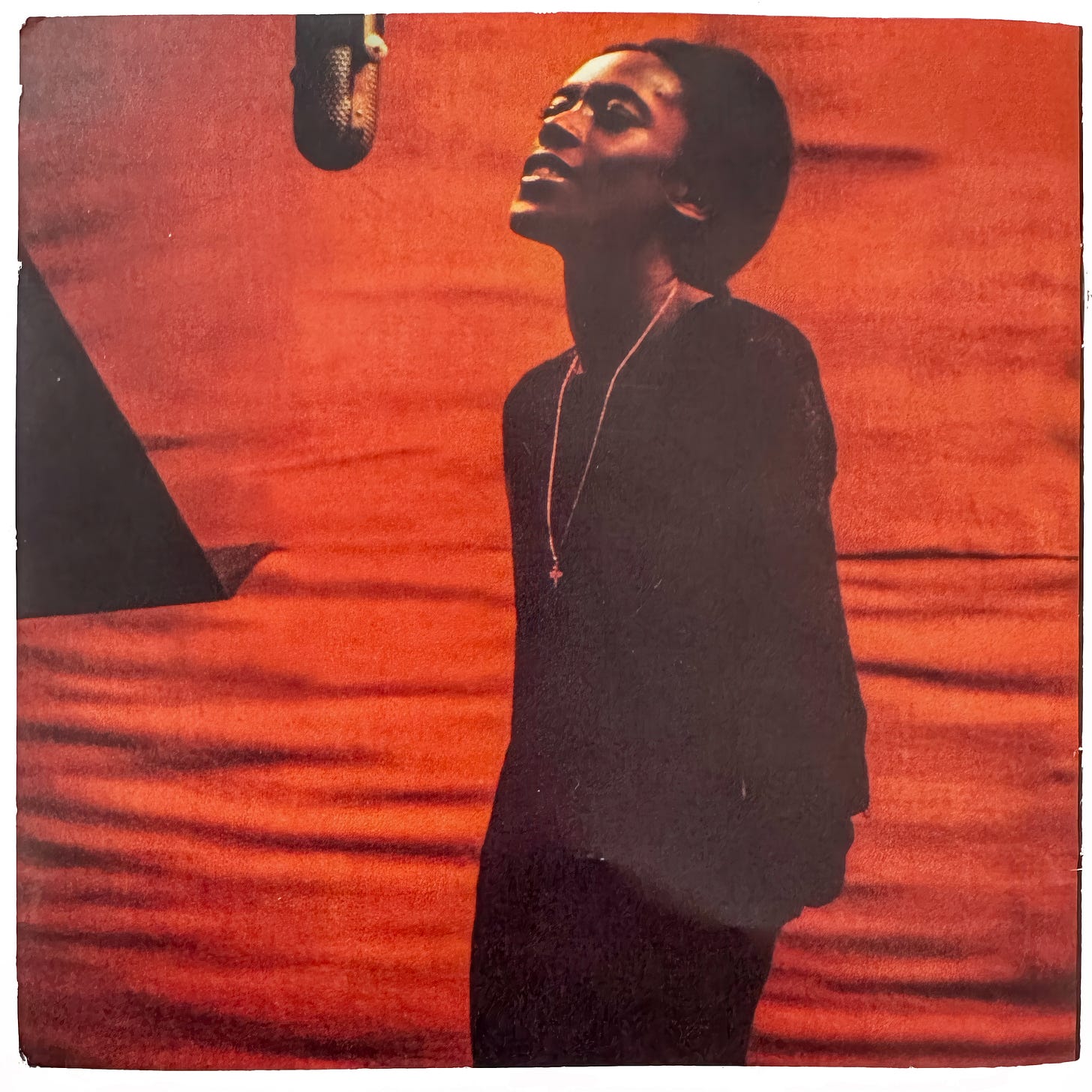

Ann Peebles was born in 1947 and raised in St. Louis, where her father was minister of music at First Baptist Church and director of the Peebles Choir, established by Peebles’s grandfather. Peebles was nine, she remembered in an interview conducted by Maria Granditsky, when she was brought into the choir, and through the group’s participation in gospel package tours, she met lifelong heroes including the Soul Stirrers and Mahalia Jackson. Her parents neither promoted nor forbade secular music, and in various interviews, Peebles cites a spectrum of R&B, blues, jazz, and country influences: Nancy Wilson, Muddy Waters, Mary Wells, Aretha Franklin. Her mother died before Peebles started her R&B career, but her father was supportive when she started performing in St. Louis clubs. Her first big break came in 1968. She had accompanied her brother and his girlfriend on a trip to Memphis, and while in town she sat in for a tune at the Rosewood Club with trumpeter and bandleader Gene “Bowlegs” Miller. She sang “Steal Away,” Jimmy Hughes’s gospel-derived, notably frank sexual plea. Recorded in ’63 but not a hit till ’64, “Steal Away” had been a pivotal production for Rick Hall’s FAME, the Muscle Shoals studio that would soon be a magnet for leading soul singers and later host the aborted session that laid the ground for Aretha Franklin’s I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You. Hughes’s vocal on “Steal Away” builds to showstopping falsetto passages. Peebles has a more compressed range but a no less dazzling vocal instrument, sometimes graveled and intense, sometimes purring and smooth. As a dramatist she specializes in erotic realism, singing songs of lived-in longing, palpable devotion, helplessly spiteful infidelity. To judge from her later recording of “Steal Away,” she must have killed that night with Miller’s band. The next day, he led her to Willie Mitchell, with whom Peebles would make a focused but steadily evolving decade of music for Hi Records.

Memphis’s Hi was cofounded by Joe Cuoghi and in its first incarnation specialized in agreeable instrumentals. Its first hit was 1959’s “Smokie—Part 2,” a shuffle by Bill Black, the bassist best known for his fifties work with Elvis Presley. The Bill Black Combo’s mellow saxophonist, Ace Cannon, scored a few years later with the misleadingly named “Tuff.” When trumpeter and bandleader Willie Mitchell came to Hi as an artist in the early sixties, he was in his midthirties and had extensive bandstand experience as well as formal musical training from Rust College. Though he recorded only a few jazz sides, he had been inspired by Clifford Brown and Fats Navarro, and his fifties group, at least as a stomping ground for illustrious players, was something like a Memphis Jazz Messengers; Phineas Newborn, Booker Little, Charles Lloyd, George Coleman, and Frank Strozier all passed through. Under his own name, Mitchell had some instrumental R&B hits of his own, but by the midsixties he had found his chief calling as a producer of singers. Early clients were Bobby “Blue” Bland and O. V. Wright, with whom Mitchell would have a long and fruitful association, mostly on records for Back Beat, a subsidiary of Duke/Peacock. While working freelance for a various labels, Mitchell started doing A&R for Hi, moving the label toward R&B, and in 1970, following Cuoghi’s death and deals cut with the label’s other interested parties, he became Hi’s visionary executive. The label released Peebles’s first single, “Walk Away” backed with “I Can’t Let You Go,” in March of ’69, before that transfer of power was sealed and a month before the Hi debut of Al Green, who would soon become the label’s flagship artist.

Both “Walk Away” and “I Can’t Let You Go” were written by Oliver Sain, one of Peebles’s mentors from her St. Louis R&B apprenticeship. The A-side is a shouting love-triangle ballad on which you can hear the imprint of Solomon Burke and of Aretha Franklin’s version of “Drown in My Own Tears.” The flip is hard and driving, its raspy, overdriven vocal bringing to mind Wilson Pickett or Tina Turner. Though Mitchell wouldn’t be able to set up Hi as a staffed, lightly industrial nine-to-five operation until the following year, Hi’s house band was already fiercely in place. The rhythm section, one of the great studio bands, was made up of Howard Grimes on drums, and brothers Leroy, Charles, and Mabon Lewis “Teenie” Hodges respectively on bass, organ and piano, and guitar. A few years later, Archie Turner would often join on acoustic and electric pianos. Al Jackson, a veteran of Booker T. & the M.G.’s and many Stax/Volt sessions, also drummed on many Hi sessions in tandem with the younger Grimes, but Grimes worked alone on Peebles’s sides. The Hodges brothers were in their early twenties when they cut “Walk Away,” Peebles’s contemporaries, in other words, or a few years older, and these early records sound so youthful and vigorous, you feel pressured to raise the rate on their car insurance. Everything is controlled and economical, which is why things groove so hard, but everything is also maxed, whereas later the Hi team would become adepts of soft-pedal funk. The horn section’s mainstays were trumpeter Wayne Jackson and tenor saxophonist Andrew Love, but it would sometimes be five members strong, with trombonist Jack Hale, and two more saxophones, Ed Logan on tenor, and on baritone Willie’s brother James, who, along with Willie, shared arranging duties for horns and, later, strings. The backing singers were Rhodes, Chalmers, and Rhodes: Sandra, Donna, and Charles. Later, Charles would write some of the horn and string arrangements.

The next single, “Give Me Some Credit,” has a Smokeylike sweetness and mostly cozies into D and E-minor like its doubling up in a sleeping bag. The singles did reasonably well on the R&B charts and an album followed in the summer, This Is Ann Peebles. One of its cuts, “Solid Foundation,” was cowritten by Don Bryant, whose 1968 single heralded Hi’s shift to R&B singers. His records didn’t do much, and he moved to the writing side. We’ll come back to him. Later Hi albums were put together at a more leisurely pace, but this one was cut on deadline. It has several faithfully arranged covers of recent hits. Not all of these are padding or redundant. On Peebles’s version of the Isley Brothers’ “It’s Your Thing,” listen to how Peebles whoops on beat four and remember that everyone’s part of the rhythm section. Badass. Mitchell miked the drums minimally in these days, but they’re beautifully tuned, present, and walloping. The snare sits just right in the mix, snappy not cracking, hot but never hoisted unrealistically above the kit. The Isleys wrote “It’s Your Thing” to be spacious, Swiss-cheese funk, and it’s a good early example of Hi Rhythm sinking into repetitive parts, finding their spots for fills, treating the pocket as a higher calling. “Al Jackson always told me,” Grimes said to Colin Escott, “groove and be simple—not busy.” It’s so hard to do. A lot of us practice the wrong stuff.

Other covers are less illuminating. The version of Fontella Bass’s “Rescue Me” races. Peebles and the group do right by Aretha’s “Chain of Fools,” with its wah-wah adding the refrain’s response, but “Respect” probably could have been left undisturbed. “Crazy About You Baby” descends from Little Walter’s “Can’t Hold Out Much Longer” but more immediately from Ike and Tina Turner’s version from their Outta Season album, a blues set put out earlier in ’69. When accenting a note, Peebles will often, like many of the singers she studied, bring out the grain in her voice as if polishing a walnut hutch. When she sings a straight blues, she isn’t dabbling. So these covers are often valuable. Made under time constraints, however, they’re not typically creative as arrangements. Al Green was doing covers, too, from the start of his Hi tenure, often aiming for reinvention. His first single was an ecstatic soul treatment of “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” which can’t hide and gets high, and he went on from there, stamping the Temptations or the Bee Gees or Hank Williams. But he could little help making everything an Al Green song, eventually became tireless about getting the perfect vocal take, and was Mitchell’s main project and eventual bread and butter.

Probably for financial more than artistic reasons, Mitchell called a kind of do-over on Peebles’s debut album. Part Time Love, from 1970, combines six of the best songs from This Is …, the choice covers included, the lesser once dumped, with four new songs. Of the new ones, “I’ll Get Along” is Peebles’s first cowrite, an auspicious start, and her first of two seventies songs involving dog bones. “Part Time Love,” a hit about finding a backup for a straying lover, helped establish the raw emotional terrain of many of Peebles’s singles. Another, “Generation Gap Between Us,” is an uncomfortably catchy song about domestic abuse. Part of Mitchell’s vision, most realized with Green, was to blend rough and smooth, steely and fragile, plain and fancy, earthy and refined. Talking to writer Peter Guralnick for Sweet Soul Music, Mitchell remembers steering Green after the success of “I Can’t Get Next to You,” “Tired of Being Alone,” and other early records: “I said, ‘Al, look, we got to soften you up some.’ I said, ‘You got to whisper.’” Peebles and Mitchell would also arrive at a version of that balance, but not yet. Part Time Love comes up the rough side of the mountain, sets up camp, and starts grading for a dance floor.

By the 1972 release of Peebles’s Straight from the Heart, Mitchell was fully in charge, Green had scored huge pop hits, the label was flourishing. Hi still operated, as ever, out of Royal Studios, a converted movie theater, but now Mitchell would work almost daily with the Hodges brothers, Grimes, and James Mitchell, laying down tracks with or without vocalists. The Memphis Horns, the Memphis Strings, and Rhodes, Chalmers, and Rhodes would come in to complete the growingly large-format pictures. Peebles’s third (or second and a half?) album has her biggest hit to date, the laid back but desperate “I Feel like Breaking Up Somebody’s Home,” written by Al Jackson and Timothy Matthews. It’s a blues in feeling if not in structure—Albert King’s cover adds a twelve-bar section for his solo—narrated by the other woman, lonely at home. Rain beats on her windowpane, spells out her lover’s name, foreshadows Peebles great hit from ’73. “Tonight, I cried so hard,” she sings. “I believe I caught a chill.” That makes two of us. Again, no one sounds straightjacketed, and no one overplays. To Colin Escott, Grimes said, “Willie would give us little instructions, like ‘sit in the rocking chair for me,’ and no one but us would know what he meant.” Switching perspectives in the infidelity drama, “Somebody’s on Your Case” advises setting up ramparts against the homewrecker. Bubbly and stern, it likely took inspiration from Betty Wright’s “Clean Up Woman.”

The album opens with the singer and songwriter George Jackson’s driving “Slipped, Tripped and Fell in Love.” As a Hi artist, Jackson peaked earlier in ’72 with the heartbreaking “Aretha, Sing One for Me” and would later cowrite the Bob Seger hit “Old Time Rock and Roll,” whose disco- and tango-averse narrator would “rather hear some blues or funky old soul.” Speaking of, one of Straight from the Heart’s singles is an inflamed cover of “I Pity the Fool,” the Bobby “Blue” Bland classic from 1961. “Look at the people!” Peebles screams, then drops her voice. “I know you wonder what they’re doing / They’re just standing there / Watching you make a fool of me.” Teenie Hodges’s leads are played through a fuzz box, the first I’ve detected on a Peebles record, and the sound is both of the present and nostalgic. Hi was the last of the classic Southern soul studios to become established, and though Peebles’s approach was by all means vital and commercially viable, she was at this point practicing an established vein of R&B for an audience older than she, the sort of old-school soul that would before long be positioned as blues on labels like Malaco. Renovations to her sound would follow, but gradually.

The album contains a pair of writing collaborations between Peebles and the aforementioned Don Bryant, both expressive ballads. On his own Bryant wrote “99 Lbs.,” hotter than a Loredo parking lot, as Dan Rather put it on an election night that felt plenty anxious then but now feels, in comparative memory, like a steam shower. “99 Lbs.” is the petite person’s answer to Howlin’ Wolf’s “Three Hundred Pounds of Joy,” and also a star on the trail of ninety-nine songs that would have lookout points at Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s “99½,” Wilson Pickett’s “Ninety-Nine and a Half (Won’t Do),” and Jay-Z’s “99 Problems.” Don Bryant, you can tell, is really into Ann Peebles. Their partnership had indeed turned romantic around this time and would become even more important on Peebles’s subsequent work. Peebles brought in more love songs, but she would go on singing and writing dark songs of cheating and being cheated, and perhaps we start to sense a stable ground that allows these fictions to bloom. As Flaubert wrote in a letter, “Be regular and orderly in your life, like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work.

*

If you’re of a certain age or into superannuated technology, you might have come across sixties home organs with inbuilt rhythm machines, small banks of short drum loops that could be adjusted for tempo. You could play “bossa nova,” for instance, or “rock.” Presets from stand-alone rhythm machines of that type and era fuse moodily with hand-played instruments on Vietnam-era R&B hits such as Sly & the Family Stone’s “Family Affair,” which was the lead single from There’s a Riot Goin’ On, and Timmy Thomas’s “Why Can’t We Live Together.” Stone’s single is an auteur’s collage in which Rose Stone’s vocals, Bobby Womack’s guitar, and Billy Preston electric piano join the leader’s saturated but spare foundation of rhythm machine and overdubs, most prominently Stone’s grog of vocals and bass. Partly because the rhythm machine is dynamically unchanging and occupies a relatively narrow range of frequencies, there’s a lot of room for everything else. More room for the record’s panned wah-wah guitar and Hohner Pianet (the cool third wheel of electromechanical pianos, it has no sustain pedal and fewer legit pianistic pretentions). Still more room for Stone to defy all sorts of recording and mixing niceties. The bass isn’t played with a heavy touch, but its level pushes the needle into the red, and you hear clicking percussive effects that would be obscured by a more conventional mix. Stone’s vocal, as I understand it, was sung into the mixing console’s talkback mike, in other words the microphone engineers use to communicate from the control room to the players in the studio. Talkback mikes aren’t designed for fidelity. They’re designed for saying, “How’d that one feel?” I’ll tolerate backtalk if the talkback trivia is wrong, but it sounds like a talkback mike, one of the reasons the song’s intimacy is telephonic. Its call always comes through when it’s too late not to answer.

Thomas’s single is a one-man show, a self-produced demo that, it was decided, could be polished but not bettered by full-scale production, and the entreaty is more plaintive in its truth and naivety because no one’s there to nod in agreement, not until we show up. Whether it’s Timmy Thomas or Hailu Mergia, I love this lonesome, hopeful sound of one musician and a trashy rhythm machine, grooving, anticipating the anticlimax of the flicked switch ending. Lights out. Both “Family Affair” and “Why Can’t We Live Together” seduce with groove without asking us to picture a band in a room, or any worldly room. On Parliament’s 1974 revival of “The Goose,” you do get a band in a room, the track’s bedrock rhythm machine a friendly droid in the mothership. The percolating machine on George McCrae’s soaring “Rock Your Baby,” from the same year but a different era, autosigns a founding disco document.

“I Can’t Stand the Rain,” Peebles’s biggest hit and one of her two great singles from 1973, sits in between the songs glossed above. The blippy pitter-patter at the start of “Rain” has the flavor of those early seventies electro-acoustic hybrids but uses different ingredients. It’s played by Mitchell on a set of electronic drum pads manufactured by Japan’s Mica-sonic, whose main line was affordable acoustic drum kits. The pads were laid out in a row: two pitches of conga drums, two of bongos (these are the four sounds we hear on the record), and a woodblock. It’s hard to imagine many percussionists treating the instrument as a regular gigging axe, but it could be easily transported in a tolex case. You could play the pads with sticks or mallets, but on a clip of Peebles and the Hi team performing the song on The Midnight Special, Mitchell uses his hands. The memorable part begins with four sixteenth notes and is only two bars—Mitchell muted some tracks at the top to help the hook protrude—but it isn’t a mechanical loop, at least not until it’s sampled on Missy Elliott’s “The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly).” Mitchell plays the part each time, then comes up with different ideas throughout the song, and much of what makes it so cool—aside from its strangely unnatural evocation of rain—is its jankiness, how it here and there jostles the groove and how its toylike sound and pitch salts the impeccably warm tones cooked up by Hi Rhythm. The song came about quickly. As mentioned, Peebles had already had a hit in which rain represented incessant torment, and for this one, she and Bryant got a natural reminder. They were scheduled to play a gig with B. B. King, but a thunderstorm stymied travel, leading Peebles to utter the title, or something close. Eureka. Peebles’s performance is restrained and precise. The vocal frisson comes on the phrase the rain, when she ascends an augmented sixth and moves from chest to head voice. It’s like she’s asking the rain to rise back into the clouds.

On the album I Can’t Stand the Rain, Peebles sands off much of the grit in her voice. The album has several excellent tracks—including her last single to break the R&B top 40, a soft cover of the country song “(You Keep Me) Hanging on”—and, along with “Rain,” two other masterpieces. “I’m Gonna Tear Your Playhouse Down,” by Earl Randle, is a prime example of what Emily J. Lordi, in The Meaning of Soul, called Peebles’s “cool interiority.” The song addresses a cad who’s been “playing daddy with every mama around.” With the sort of anger that’s aged into equanimity, the singer plots vivid metaphorical revenge. When will she tear this playhouse down? Pretty soon. A withheld deadline is more menacing. And it will be systematic, roooom by room. Twice we hear chimes—referencing babies and playhouses, I guess—and now Peebles gets the Memphis Strings so often heard on Green’s records. They keep bowing while all around them someone’s ripping out floorboards. “Until You Came into My Life,” by Bryant, Peebles, and Bernard Miller, is her most tender love song. With Al Green, there is often a blend of straightforward and more elaborate harmony (“We used some nice diminished ninths with Al,” Mitchell told Guralnick), but Peebles’s usually leaned to the straightforward side. Here we have a flowing, careful, and somewhat chromatic harmony in the verse, and a perfect two-chord pattern (I-ii7) for the chorus. Hear how understated Leroy Hodges’s bass is, how melodic when he spots a gap, and how the organ and strings pad so simply and effectively. Teenie Hodges makes every arpeggio and lick count. (“He’ll play a little guitar, just a taste,” Al Green told writer Robert Palmer, “but it means so much more because he puts it in the right place.”) Peebles, though unforced when pulling out all the stops, again holds back, singing with great subtly and feeling, hitting beautiful E5’s (the E a tenth above middle C) on the swooning chorus. Not every true love lasts, it’s true. But Peebles and Bryant are still together.

The Mica-sonic gets uncased for “Come to Mama,” the pounding lead track on 1975’s Tellin It. “If you need a satisfier,” Peebles sings, “let me be your pacifier.” Kind of naughty. It’s a complex band arrangement, with lots of tucked-in details I can’t identify. Grimes mostly plays it cool, so when he lays into his snare or floor tom, you feel it. There’s a rubber-bandy vibration in the low end, Leroy Hodges’s bass, maybe, or it could be a synthesizer or a treated drum. The horn arrangement surprises in spots; Archie Turner’s piano will dance across the room, then hide behind a curtain. Bob Seger’s cover is creditable, I guess, but overeager. Peebles wasn’t yet thirty, but her voice had matured significantly. It’s fuller now, smoother, maybe more flexible, less drawly and go-for-broke. In the past, she didn’t craft a persona, she mapped a neighborhood, one you could walk around in. On Tellin’ It, a bit of persona-building enters, and she’s something like a more socially acceptable Millie Jackson, particularly on “Beware.” She pulls off the role but you doubt she’s gonna ask to keep the costume. Besides “Come to Mama,” the highlight is Bryant and Peebles’s “I Needed Somebody,” an extended gospel-drenched narrative. All sorts of heavy stuff in that one: regret, betrayal, redemption, family pain, scores more tenor-sax fills than a Peebles record had previously allowed. The backing singers must be the Duncan Sisters (Rhodes, Chalmers, and Rhodes weren’t gospel singers). Listening to the album, I start to think the Peebles-Bryant collaboration is by this time the most electric and interesting one, and that Mitchell is stifling them.

Maybe not. By 1977, the landscape had changed a lot. William Bell, Joe Tex, and Johnnie Taylor were still scoring R&B hits, but so were Chic and the Bee Gees, and much of the big-selling R&B was lithe, urbane, and lavishly produced. Something like the Brothers Johnson cover of “Strawberry Letter 23,” produced by Quincy Jones, was locked in place by armies of specialized professionals. If This Is Heaven, from that year, is the most elaborate of Peebles’s albums so far. The core group stands, but there are additional players, strings everywhere, disco beats and layered talk-show funk. Clavinets turn up, the horn charts are slicker (and very good), and Mitchell can use more tracks and mikes now, so while the sound is still warm and tube driven, we get more definition in the kick drum, for instance, and it sounds great. The title track, by Earl Randle and Willie Mitchell, is about a relationship run aground, and Peebles sings much of it in her upper register, floating elegantly over the midtempo disco. As a lyricist and interpreter, Peebles wants, I think, at least one line of flinty conversational poetry. She gets it here. “If this is heaven,” she coos, “lead me to hell.” You can sing a lot of run-of-the-mill stuff, but if you want us to cry, you need one line like that. On that note, the album’s other jewel is a cover of O. V. Wright’s “You’re Gonna Make Me Cry,” which Mitchell produced in 1965. The song is credited to Deadric Malone, a pseudonym for Duke/Peacock honcho Don Robey, but his writing credits were often fabricated and exploitative. It must have been moving for Mitchell to return to the Genesis of his production career, and everyone rises to the occasion. If you’re a bassist or drummer wondering what to do on 6/8 ballad, it couldn’t hurt to put on this one and focus on Leroy Hodges’s bass and Howard Grimes’s drums, his kick in particular. Peebles is virtuosic. The album has an additional guitarist, Michael Toles (his is the wah on “Shaft”) joining Teenie Hodges, and I believe it’s him using a volume pedal and then, later, arrestingly, a talk box. If you’ve seen Peter Frampton or Roger Troutman playing music with plastic tubes dangling from the sides of their mouths, you know the sound. It’s amazing here, not a joke, though I do get some of Robin Williams’s impression of Elmer Fudd singing Bruce Springsteen. Peebles’s last album for Hi, 1979’s aptly titled The Handwriting Is on the Wall, is a bit exhausted, or I am. But I think the former.

Peebles took a long break from music while raising children. She returned in the nineties, and that material deserves attention as well, but I’ll stick to the Hi records, much of which have been lovingly reissued by Fat Possum Records. After suffering a stroke in 2012, Peebles retired. Don Bryant still performs. Last night I searched out some pictures of them together during their later years while I listened again to “Until You Came into My Life.” You try it. A love song like this, it’s hard to do. You can just say what you feel, but, sad to report, that’s probably not enough. “You can’t get at a sunset naming colors,” the poet James Schuyler wrote. So Ann Peebles and Don Bryant and Willie Mitchell and Hi Rhythm and everyone give us something more, and there it is, the sunset, not the one from the calendar.

For you opened up my eyes, and you made me see …

None of my friends can make this out, it seems, but if you turn up the song as it fades, you can faintly hear Willie Mitchell through the talkback mike. He says, “How’d that one feel?”

Great post on a fabulous artist.

This is fantastic! Thank you!