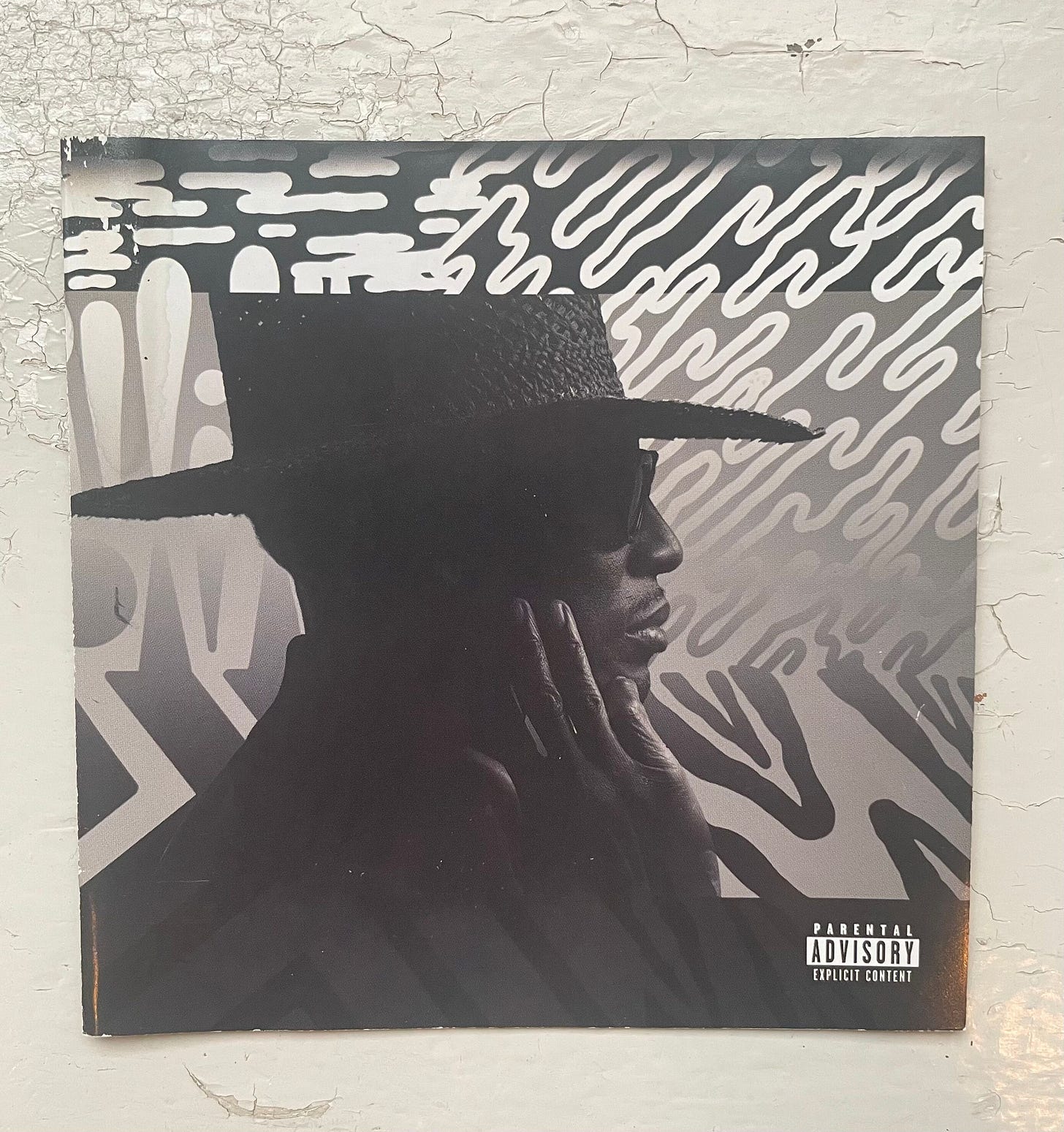

An "Archival" Piece on Raphael Saadiq

An overview and appreciation of the R&B performer and producer

This article was first published in early 2020 by City Pages, whose archive is hard or impossible to access.

Raphael Saadiq’s musical apprenticeship started early: he took over the bass chair for the Gospel Hummingbirds before he was a teenager and a few years later earned a spot in fellow Oaklander Sheila E.’s band, which opened most of the dates on Prince’s Parade tour. After that, Saadiq, who was born Charles Ray Wiggins, cofounded Tony! Toni! Toné!—the exclamation points were later dropped from the band’s album art, even as the music got more exciting—with brother D’wayne Wiggins and cousin Timothy Christian Riley. Their first single, the spring of 1988’s “Little Walter,” was a new jack swing touchstone written by the group in collaboration with producers Denzil Foster and Thomas McElroy, who had hit earlier with Timex Social Club and Club Nouveau.

The song’s amalgam of references predicts much of Saadiq’s subsequent work with the band and on his own: history minded but not merely nostalgic, out of step but in the present. Its chorus melody is borrowed from “Wade in the Water,” the spiritual often revived during the Civil Rights era and inserted into the Top 40 by Ramsey Lewis’s funky instrumental. Contrasting this foundation is a minatory keyboard riff built on the harmonic minor scale. (In the fall of ’88, the bass line of Bobby Brown’s “My Prerogative” would also use the harmonic minor scale in A minor—probably a coincidence, given the proximity of release, but at least for a few seasons somewhat exotic minors helped define new jack swing.) “Little Walter” is an old-fashioned story song: the titular character—the name must come from the great Chicago harmonica player, but the connection is strictly nominal—is the narrator’s new roommate, an unflappable scofflaw who refuses to pay his share of the rent despite a growingly lavish lifestyle financed by a “hobby” we take to be criminal. Another precedent the song established for the band and Saadiq is a concern with money problems and the have-nots: “Just because he drives a Porsche, and, girl, I drove a Nova,” D’wayne sang on a later single, “The Blues,” and throughout you sense the mandate is to make exquisitely engineered music for Nova drivers.

By the song’s end, Walter is murdered by creditors or rivals. The menacing but essentially light song doesn’t aim for tragic effects, but its pleading chorus treats Walter sympathetically, and you can imagine him being among the figures who populate Saadiq’s most recent album, Jimmy Lee, a unified set of songs, drawn from familial history, about addiction, faith, mass incarceration, and American racism.

Jimmy Lee is the weightiest album in a body of work that includes several triumphs and few missteps. Tony Toni Toné’s largely self-produced second album, The Revival, is spotty but impressively rangy and produced four No. 1 R&B hits, including the effervescent “The Blues” and the straining “It Never Rains (in Southern California).” The former tune is a good example of the vocal interplay between D’Wayne, a baritone with great time feel, and Raphael, a tenor in the casual way pop voices are classified, or a baritone who pushes it. The Revival has the sixty-watt snares and hopped-up tempos of early ’90s R&B, but its retro references point the way to neo-soul while expanding new jack hybridization. It’s likely another coincidence, but the mix of blues, hip-hop, and funk on “Let’s Have a Good Time,” one of three tunes for which Foster and McElroy returned, foreshadows the similar and more elegant braid Teddy Riley and his collaborators cooked up for “No Diggity.” Tony Toni Toné peaked with Sons of Soul, one of the great albums of the ’90s: expertly paced, blemished only by “My Ex-Girlfriend” (she’s better off without him), commanding in all its modes, from the swinging kiss-off “If I Had No Loot” to the gargantuan slow jam “Anniversary.”

The group was often positioned as a throwback to the funk era, an autonomous band of singer-writer-instrumentalists rather than a vocal group working with producers, writers, and session players (a tradition no less honorable), but you wouldn’t immediately get that from the first three records: the group used (its own) drum programming more often than acoustic drums and wasn’t especially interested in documenting a live sound or reenacting old-fangled recording techniques—Saadiq would get to that later. But the group’s fourth and last album, House of Music, dug into its last-band-standing rep, its grooves redolent of the ’70s but with a fat burble very much time-stamped 1996. Among other things, it shows the group’s relaxed gifts as pasticheurs—the Al Green/Willie Mitchell tribute, “Thinking of You”—and its ongoing knack for borrowing and juxtaposition, such as how “Let’s Get Down” brings together DJ Quik, an acoustic guitar figure laid over car-rattling bass, and a chorus derived from “Smells Like Teen Spirit.”

Since Tony Toni Toné’s breakup, Saadiq has made a one-off with the semi-supergroup Lucy Pearl, five solo albums, and several display cases of high-profile productions, including cowriting and coproduction credits for Solange’s “Cranes in the Sky” and D’Angelo’s “Lady” and “Untitled (How Does It Feel).” The “gospeldelic” Instant Vintage, from 2002, is a lavish neo-soul response from one of the genre’s progenitors-not-practitioners, akin to those late ’70s Lou Reed and Iggy Pop albums wrestling with punk. If you’re using it as mood music, it’s a good length, and gorgeous; for a concentrated listen, it’s a touch overlong and underwritten. Saadiq’s lyrics, for one, don’t always seem to have undergone multiple revisions, though he’s singing them better than ever. Still, the album is a wonder of groove, tone, and harmony that sometimes settles into ambiguous profundity, especially on the strange reminiscence “Charlie Ray.” There, the four-year-old Saadiq crawls (at four?) into the living room, where his father accidentally steps on his hand: “That’s when I met my soul,” Saadiq repeats. College students assigned to read Aristotle’s De Anima should be given “Charlie Ray” as a supplement. The follow-up, Ray Ray, presented as a soundtrack to an imaginary blaxploitation movie, is definitely underwritten.

Through this point, much of Saadiq’s work sounded like old music but not like old records. That changed with his next two albums, 2008’s The Way I See It and 2011’s Stone Rollin’. The handsomely budgeted Way I See It has a Chi-Lites rewrite and pre-Beatle 6/8 ballad, but most of the album imagines an unearthed mid-’60s Motown session, and Saadiq and company—he particularly credits engineer Charles Brungardt—fastidiously worked to get every snappy snare, overdriven vocal, harp, tambourine, blues lick, and bell-like arpeggio to sound more or less like Johnson was still in office and Berry Gordy was signing the checks. As on Instant Vintage, when you hear a string arrangement, it’s because Saadiq hired a room full of people, plus arrangers, concert masters, and copyists instead of someone with a keyboard and a decent sense of harmony. The songs are short and propulsive, the lyrics plain but sturdy, and they speak to the present despite the studio patina, for instance on the post-Katrina “Big Easy.” For the rawer Stone Rollin’ Saadiq moved the references up a few years and made the sort of Mellotroned rock record you’d hear at the Temptations’ psychedelic shack, a party record on the edge of desperation. The cathartically grand “Go to Hell” starts, “Here’s the situation, yes, the devil knows me well,” while another refrain goes, “I’m livin’ on daydreams, I’m gonna buy me something I can’t afford.” Both albums reverberate more than replicate.

Jimmy Lee’s namesake is one of the Saadiq’s thirteen siblings, four of whom died young: brother Alvie was murdered in a dispute with a family member when Raphael was a boy; Jimmy Lee Baker, much older than Raphael, had a long struggle with heroin that eventually led to a fatal overdose; another brother, Desmond, a suicide, also battled chemical dependency; a sister, Sarah, was killed after backing her car into a police chase. On the album, Saadiq sometimes deals with this history literally (“I love Jimmy but Jimmy smoke crack and sold my horn,” he sings on the pulverizing “My Walk,” a collaboration with Charlie Bereal), but for the most part Jimmy serves as a representative figure.

Saadiq draws again on wide influences from gospel to hip-hop but discards the stone-washing effects of the previous two albums for a singular but more contemporary sound. It often foregrounds Saadiq’s slippery bass lines—he’s a multi-instrumentalist but a bassist first, and a great one. Aptly for an album largely about addiction, the sound toggles between blissed out and on edge. The tracks segue (as in “proceed without pause”) from one to another, the abrupt shifts building tension, the vantage moving from private and interpersonal stories (pain, pleasure, love, loyalty, betrayal) to spiritual and societal matters. It starts with its weakest song, the melodramatic “Sinner’s Prayer,” but gets stranger and more affecting as it progresses. The turning point is “Belongs to God,” a Saadiq tune first quietly released as “My Body Belongs to God” on Palm of His Hand, a 2017 album by Saadiq’s octogenarian uncle, the Rev. Elijah Baker Sr. The shorter, remixed version on Jimmy Lee features the same perfect Baker vocal (check out his vocal dip at 1:15), and here it helps, well, incorporate themes: addiction works on bodies, after all, as does music, and, as we’re reminded a few cuts later, it’s bodies that are imprisoned for drug offenses, Black bodies in grossly disproportionate numbers.

That just-mentioned cut is “Rikers Island,” a climactic anthem of Samson-like power against racist mass incarceration, Saadiq doing call and response with his own own-man, multi-tracked choir. The song ends with a slammed cell door, then the vamp continues on a pitch-shifting guitar, and actor and writer Daniel J. Watts enters with a unsparing and inspiring monologue. When Kendrick Lamar, hardly billed, turns up for an introspective postlude, it’s icing on the arc. What a beautiful record, what an amazing career.